Reading rhythms in sheet music

At the time of writing, the majority of resources on reading rhythms in sheet music base their approach on conscious analysis. However, the final goal of rhythm reading is not to logically analyse, but to audiate. Rhythmic audiation is the ability to look at some notation and have it immediately play back in your head, much like words 'pronounce' themselves to you as you read English.

The logical and subconscious minds are largely separate, and understanding what rhythm notation logically means will do little to help you read it. Rather, the skill of audiating rhythm notation can be developed more easily if you focus on training the subconscious directly through mimicry.

One can imitate rhythms by ear or watch someone performing a rhythm by clapping or dancing, and copy what they are doing. Through repetition over time, patterns become innate, akin to an audio 'muscle memory'.

Once a pattern has been internalised, it is easy to associate it with the equivalent representation in music notation, without ever needing to analyse the notation.

Putting it into practice

So let's put this idea into practice. Listen to the following rhythm, and as you do so, mirror the sound that you are hearing:

- Vocalise it using 'da, da' sounds or similar.

- You could also clap or otherwise move to the rhythm.

After repeating this a few times, after a few minutes, or possibly a day, you'll be able to perform the rhythm without the audio reference. At that point, imagine the same sound and/or body movement in your head while also performing it physically. Once that gets easy, try just to hear (audiate) the rhythm internally.

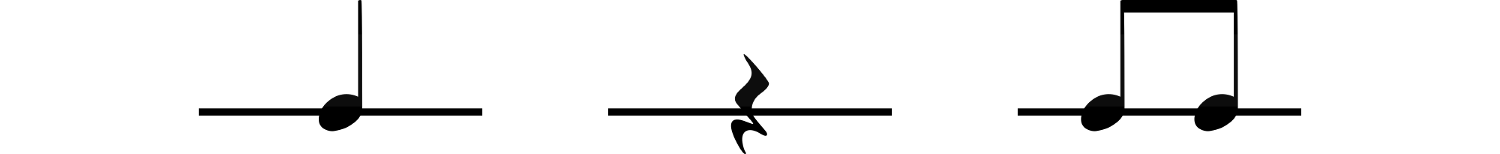

Once the rhythm has been internalised, it is straightforward to associate it with the equivalent music notation shown below:

Practice performing the rhythm while looking at the notation. After a day or few of practice, you'll find that upon looking at the notation, the equivalent rhythm starts playing back to you in your mind's ear.

It may take some time for this to happen, and you may not see results until you sleep. Persistence and regularity are critical for this process to work because the mind only remembers things that you're using regularly.

But this process is analogous to how children learn to read. One's first words are learned by listening to their parents. Reading then comes later, as we associate known sounds with the sight of letters and words. That this happens is obvious from languages like English or French, as many words are not written phonetically.

Rhythm figures

Intuition could suggest that learning to read rhythm notation using this approach would entail learning the rhythm of every song you want to play from start to finish from scratch. It could thus seem very complex, but this assumption is incorrect.

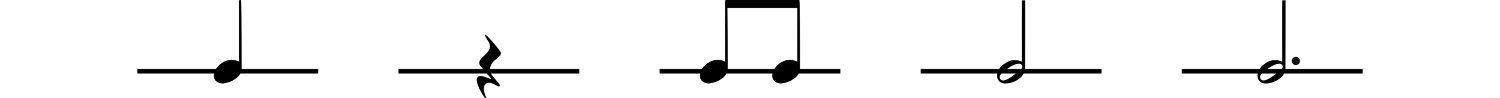

While rhythms are unique on a large scale, the story is different if we zoom in. Rhythms can be broken down into figures, short patterns analogous to words. The example above is built from the two figures shown below.

The key point is that many rhythms can be built from a pool of figures, just like different books can be written in the words of a common language. In this regard, figures are like Lego bricks; they can be assembled in any order to form arbitrary rhythms.

By developing an intuition for the sound of different figures, how those figures sound in relation to an underlying beat, as well as how they sound when played before or after other figures, you will be able to read any rhythm constructed from those figures.

The examples in this article intentionally use simple figures to demonstrate this concept in a straightforward and comprehensible way, but the learning process illustrated can be applied to rhythms of arbitrary complexity.

Figures in the context of a beat

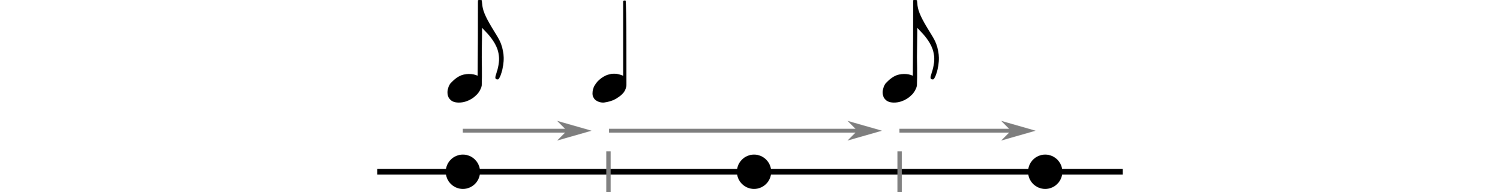

A rhythm figure can relate to a beat in various ways; it may use notes that subdivide the beat, span multiple beats, or rests that play nothing for some period of time. When learning to read music, it is essential to develop an intuitive understanding of this relationship.

You can begin to get a sense for that relationship by preceding a figure with a context. Regardless of the time signature, there will be a note symbol that has the duration of one beat. You can put any figure into context by prefixing it with a series of these. For instance, if the figure is in 4/4 time, you can prefix it with a series of quarter notes.

Next, look through some sheet music to identify rhythm figures. Write them out in a music notation software like MuseScore, adding preceding notes to put it into context. The result will look something like this:

Example 1

Example 2

Example 3

Having familiarity with a prefixed figure, the next step is to learn to audiate the figure with the beat simultaneously. This way, you audiate both the notes of the figure and the sound of the beat (metronome) underneath it.

An option is to hear the figure played over a metronome on repeat. Audiate everything you hear (the notes and the metronome) in your mind until you can audiate it without the audio reference.

A second option is to practice tapping the beat with one hand, while simultaneously performing the rhythm of the figure with your other hand. To do this, I'd also recommend starting with an audio version of the rhythm played over a metronome. Proceed as follows:

- First, tap the rhythm of the metronome on a table with one of your hands.

- Next, tap the rhythm of the figure on a table using your other hand. Focus on this alone, without the hand you were tapping the metronome with.

- Once the two can be done separately, try to perform them at the same time.

When you can perform this, next try audiating the sound you hear while performing it, and then drop the physical performance.

Figures in the context of other figures

The other aspect to learn is how one figure sounds when following another figure. For example, working with the three figures—quarter note, quarter rest, and a pair of eighth notes—how do they sound when paired in different combinations?

It is easy to practice this exhaustively by choosing one of these and sequentially playing all of the figures after it:

- Quarter followed by quarter.

- Quarter followed by a pair of eighth notes.

- Quarter followed by quarter rest.

The figures sound like this:

Listen to each example one by one and clap it 10 to 20 times, until it becomes automatic.

Then, if you repeat the same process starting with the other two figures, you can list every possible combination of these figures. For the three figures we have been using so far, there are nine possible combinations: the three above and the six following.

By practising the figures in this way, you internalise what every figure sounds like when it follows every other from the set. Thus, when you read rhythms built from them as you move from note to note, you'll always know how it should sound. Here's a simple example to try it out:

Then try assembling some of your own rhythms that incorporate these figures. This would also be an excellent jumping off point to start playing with improvisation.

Figures in different time signatures

So far, we have just been discussing figures in their own right, but how do they relate to a time signature?

As we explored in The essence of rhythm notation, a time signature tells you how many and which kind of note you'll find in a bar of music. For example, the time signature '4/4' means 'four quarter notes',

The patterns of notes that you will find within a given time signature are based on this structure. For example, for rhythms in 4/4 time, you'll often see patterns like the following:

In different time signatures, the patterns of notes that you encounter will also be different. Here, for example, are some patterns that you'll often see in 3/4 time:

You can read rhythms in different time signatures just using the relative relationships between the notes, as was introduced earlier in the article.

Rather, the characteristic feel of these time signatures, whether the rhythm is felt in groups of three or four, arises from the patterns of notes used. For example, notice how the pairs of eighth notes in the examples have been placed to highlight groupings into four and into three.

Real performances also communicate grouping through how a player emphasises the notes. As noted in the article Getting Rhythm, this is a pattern you'll often hear with music in 4/4:

Strong, weak, strong, weak ...

On the ocarina, this typically occurs through the use of ornamentation. There are many different emphasis patterns that occur in real music, though. It is worthwhile to find both sheet music for a few songs along with performances and try the following:

- Look at the sheet music to see the time signature and general structure.

- Listen to the music and hear the emphasis patterns that are being used.

- Notice how the structure of the notes and emphasis in the performance relate to the notation. There will be aspects in the audio that are not notated.

Try clapping the rhythms from the sheet music over the recording, reproducing strong and weak beats by clapping harder or softer. Notice how these patterns relate to the patterns found in the notation. It can be helpful to use a digital audio workstation to loop small parts of a recording, see Playing your favourite songs on the ocarina for some tips.

How to develop your rhythmic vocabulary

Developing a large rhythmic vocabulary that enables you to read the majority of rhythms you encounter is simply a matter of applying the processes discussed. I'd suggest starting with a small selection of figures, such as:

Practice these as we explored earlier in the article, following each figure with every other one, to internalise the possibility space of rhythms they can represent.

By doing this and practising rhythms built from those figures in different time signatures, you will soon reach a point where you can audiate any rhythm that can be created from this subset without needing to think.

And then it's just a matter of gradually introducing and practising new figures. But where do you find figures to practice?

- It's easy to find extensive collections of rhythm exercises in the form of books, websites, and apps, from which figures can be sourced.

- The music you're learning is also a great place to source rhythm figures, with a clear advantage of helping to improve your ability to play the music you want to play.

Just be mindful that sourcing rhythms from only a single music genre can limit the scope of what you learn. Ensure that you reference a diverse range of music to gain a comprehensive understanding of the rhythms used in real-world music.

The following are examples of things you'll encounter, and are a good starting point:

Groups of eighth and sixteenth notes

Beamed groups of eighth and sixteenth notes are very obvious figures, and these patterns show up over and over again in numerous genres of music.

Dotted rhythms

It's really common to see rhythms formed from a dotted note immediately followed by another note that brings the rhythm back into alignment with the beat, such as a dotted quarter note followed by an eighth note. The same idea applies to other note durations.

And figures are often encountered with these same notes in the opposite order:

Triplets

A triplet is when three notes are played in the time duration of two, such as three quarter notes in the time of two. They have quite a distinctive sound:

The relationship between the triplet and a straight beat can be heard easily by preceding it with a context as above. You may initially find it helpful to connect the triplet rhythm with a three-syllable word, like 'pine-ap-le' or 'ja-fa-cake'.

Rhythms using ties

A tie joins the rhythmic value of two notes together into a single note. Ties are most often seen in rhythms where a note is played across a bar line:

The durations that are notated using ties are frequently equivalent to those of common note symbols, and the tied notes in this rhythm are equivalent to a half note. Using ties for cross-bar notes improves readability because it means that the first note symbol after a bar line always aligns with the downbeat.

Learning to audiate tied notes is much the same as discussed previously: isolate the tied note pair as a figure and practise it in the context of other figures. Here, it has been prefixed and followed by a quarter note to match the usage in the original rhythm; those can be substituted for any other figures to practice it in different contexts.

Once you're comfortable audiating the tied note figure in relation to some other figures, try reading it in the context of the original rhythm. It may feel different because the overall grouping and emphasis within the context of the rhythm are different, even though the relative note durations are the same.

Tied rhythms that include notes of different durations can be approached similarly. For instance, here is a rhythm with a tie to an eighth note, equivalent to a dotted quarter note and an eighth note.

Just isolate the tied pattern as a figure, and practise it by listening to and clapping the rhythm while looking at the notation. I'd recommend forming such figures to contain a uniform number of beats so they can be looped seamlessly.

Ties are also used to notate rhythms that cannot be notated using the standard note symbols alone, and they can be practised in the same way, isolating the tied patterns into sensible figures, listening to them while looking at the notation, then putting them into different time signatures.

Syncopations

Think about what happens if you follow an eighth note with a quarter note in 2/4, 3/4 or 4/4. The quarter note would be delayed such that it 'bridges over' the next beat and shifts the emphasis onto the offbeat. This is called syncopation.

Here are some examples of common syncopations:

Syncopated rhythms are prevalent in various genres of music, including reggae and electronic dance music. Can you find any in the music you listen to?

In different time signatures, what is considered syncopated changes due to the location of the beat also changing.

Figures in compound time (3/8, 6/8, 9/8, and 12/8)

As mentioned in The Essence of Rhythm Notation, the time signatures 3/8, 6/8, 9/8, and 12/8 are used to notate music where each beat is split into three sub-beats.

The figures found in these time signatures are typically simple, consisting of the beamed group of three eighth notes and variations on that:

Note that the rhythmic subdivision within a group of three eighth notes in these time signatures is frequently performed unevenly, the first note of the group being played slightly longer than written, and the other two notes are fit into the remaining time.

This is called either 'lilt' or 'swing', depending on the musical idiom, and is done to emphasise the downbeat. The amount of lengthening is subtle, typically less than a dotted eighth note. It isn't easy to notate, and never is is in my experience.

Whether this is done depends on the idiom and the performer. It can often be heard in Irish jig playing and is straightforward to learn by listening to a performer and imitating them.

Beats on the half note (2/2, 3/2, and 4/2)

Not all music assigns the quarter note to the beat. Time signatures with a '2' at the bottom are commonly used to represent a rhythm, where the beat is instead assigned to the half note. For example, in 2/2, you'd hear just one metronome click for each half note, instead of two that you'd hear in 4/4.

Learning how to audiate sheet music in these time signatures is straightforward because the relationships between the notes symbols are the same. A quarter note is still half as long as a half note, only the relationship to the beat has changed.

Because music notation is relational in this regard, it is valuable to learn how the proportional differences between notes sound (for example, what it sounds like when a note is twice as long as another) as one skill. Then, how different combinations of notes sound in relation to a beat can be learned separately.

It is possible to know the sound of any rhythm just from the relative lengths of notes, but this doesn't indicate where the emphasis should be. To learn that, use a music notation software and write out some rhythms using figures that you're familiar with in 2/2 instead of 4/4. Listen to it played back with a half-note metronome enabled, and practice audiating both the metronome and the beat.

The primary difference resulting from this change in assignment is to double the effective tempo and shift the emphasis. For that reason, the figures that you encounter within these time signatures are essentially the same as time signatures like 4/4.

It may not be clear, though, why music would do this, instead of simply using shorter note values in the 2/4, 3/4, and 4/4 time signatures. To some extent, this is related to history because it was once common to notate music with longer note symbols. There was a shift towards assigning a shorter note symbol to the beat due to cultural trends.

However, assigning a different note symbol to the beat can also improve readability and clarify communication. For example, if some music is composed using small subdivisions of the beat, shifting the beat to a longer note duration could eliminate the need to use 32nd or 64th notes.

Using different time signatures can also help convey distinct playing styles. Waltzes, mazurkas and triple hornpipes are all in groups of three beats, but are played differently. Using the 3/2 time signature for triple hornpipes helps to differentiate them.

These time signatures don't always mean that the half notes are assigned to the beat. A metronome mark may indicate something else, and a recording of a performance is always the most reliable reference for how something is meant to sound.

Closing

Learning to read rhythms is a process of practising different rhythmic patterns until they have been internalised. Once you have some figures, they may be practised in various combinations with other figures, allowing them to be audiated and performed from muscle memory in any order.

Learning how to read a diverse set of rhythms easily is mostly a matter of internalising the possibility space of rhythms that sheet music can represent. This can be done by starting with a few figures and practising them in all possible orders.

The order in which figures are learned doesn't matter that much because anything you learn is going to expand your coverage of the possibility space. It's perfectly fine for a beginner to jump directly to learning complex figure patterns if they are needed to play a song they love.