Utilising common melodic patterns for reading sheet music

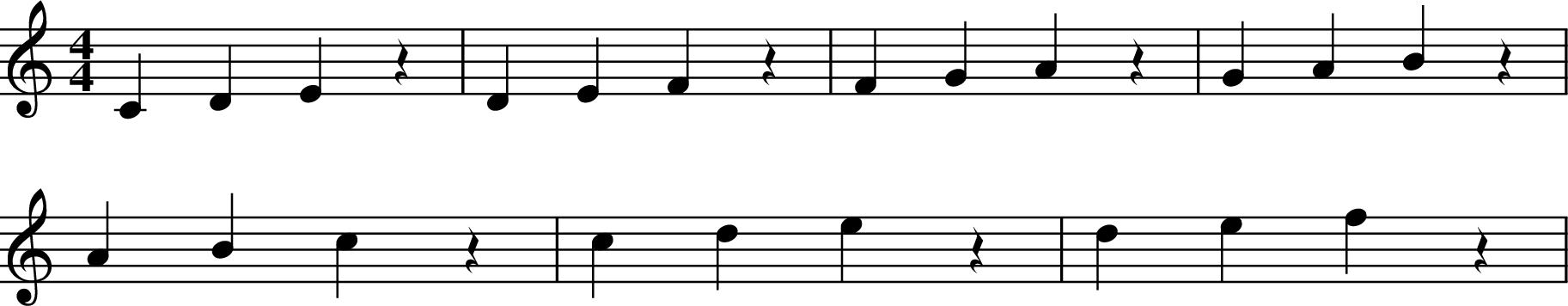

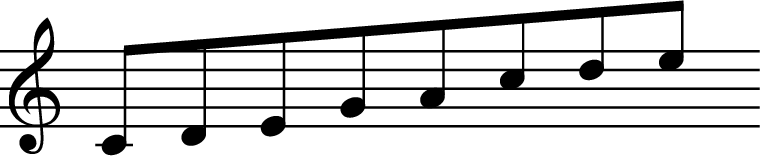

The notes found in music are not random. If you look at this notation, for instance, what do you see?

It shows the notes G, A, G, d, e, and d, but there is another way of viewing them. This is two repetitions of a simple pattern:

- Play a note.

- Play the note one step higher in the scale.

- Play the starting note again.

With some experience, you can learn to read music by recognising these patterns. If you practice them over the full range of your instrument, they can easily be performed from muscle memory as a unit, without the need to process the individual notes.

Let's explore common melodic patterns and see how they can be used in sight reading.

Scale runs

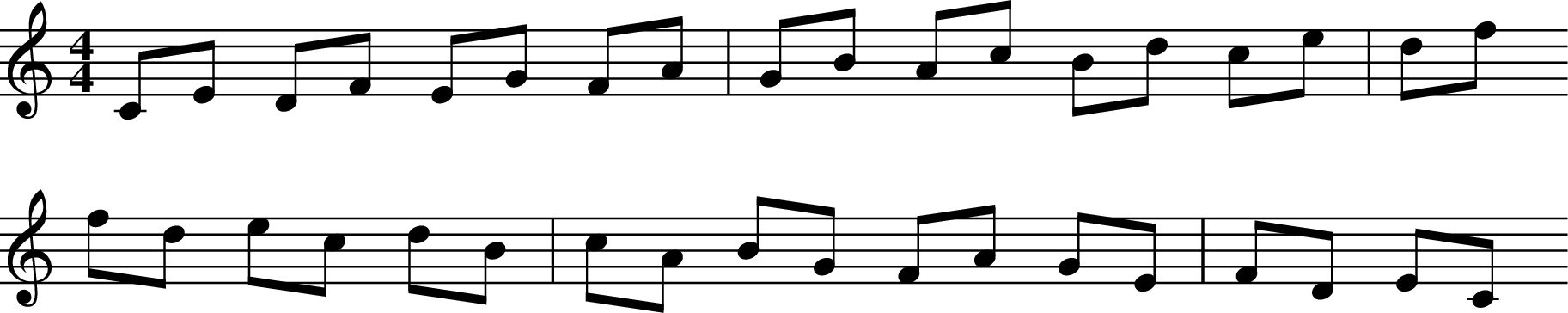

The most basic pattern you'll see in sheet music is a scale run, when the notes of a scale are played in ascending or descending order:

You may know a scale as being played octave to octave, but most scale runs in real music consist of a short slice only two, three, or four notes long. There are a number of them in the first part of Jim Ward's Jig, which have been marked with slurs below:

Jim Ward's Jig

If you look at some of the sheet music you play, it should be easy to find some scale runs. They often appear as beamed groups, but you'll also find them between individual notes, across two groups of beamed notes, as well as between notes on either side of a bar line.

A useful feature of these short melodic patterns is that they can easily be shifted up and down within the scale. You may practice playing a three-note scale starting from every note within the main range of an alto C ocarina:

After practising that for a few days, performing the pattern from any note will become effortless. Then, when you see the pattern in notation, you automatically know what to do. I'd recommend practising ascending and descending scale runs of two, three, and four notes, in every key you commonly encounter.

Diatonic intervals

An interval is the distance between two notes, and diatonic intervals name the distances between the notes of a single scale, like C Major or E minor. There are seven diatonic intervals we commonly encounter in music:

Seconds

In sheet music, a second is the interval between any adjacent line and space. The second is the smallest diatonic interval.

Thirds

Thirds are easily recognised as they are the interval between two adjacent lines or adjacent spaces. They are very commonly seen, as arpeggios are based on thirds.

Fourths

A fourth is a movement of three staff positions. That is, from a line to the space following the next line upwards or downwards, or from a space to the line following the next space upwards or downwards. A fourth is also the interval between the fifth of a chord and the octave above.

Fifths

A fifth is the distance between three adjacent lines or three adjacent spaces. It is also the same as two thirds added together.

Sixths

A sixth is the interval between three lines plus one, or three spaces plus one.

Sevenths

A seventh is four lines or four spaces on the staff.

Octaves

The interval between four lines plus one, or four spaces plus one, is an octave.

Performing and recognising diatonic intervals

It is straightforward to practice performing the intervals of a scale in every possible position on an instrument. For example, to do so with a melodic third, you start at the bottom of the scale, then practice sequentially, moving up by two notes in the scale, and then back down again by one note.

This process can be repeated for the other intervals within this scale and any other scales you commonly use. The rest of the C major scale intervals can be found in the exercises section: diatonic intervals for ocarina.

Once you can perform the intervals from muscle memory, the next step is learning to recognise them within sheet music. You could possibly choose two or three intervals initially, and have a friend write them for you on some music paper:

- Get some blank manuscript paper (easy to find online).

- Ask a friend to draw notes at different intervals. Use the range within the staff and ledger lines.

- As each interval is drawn, say its name aloud and have your friend tell you if you were correct.

There are also music practice apps that will generate random intervals in notation. Another option is to look at any sheet music you have, and instead of looking at the absolute positions of the notes, look at the intervals between them.

Arpeggios

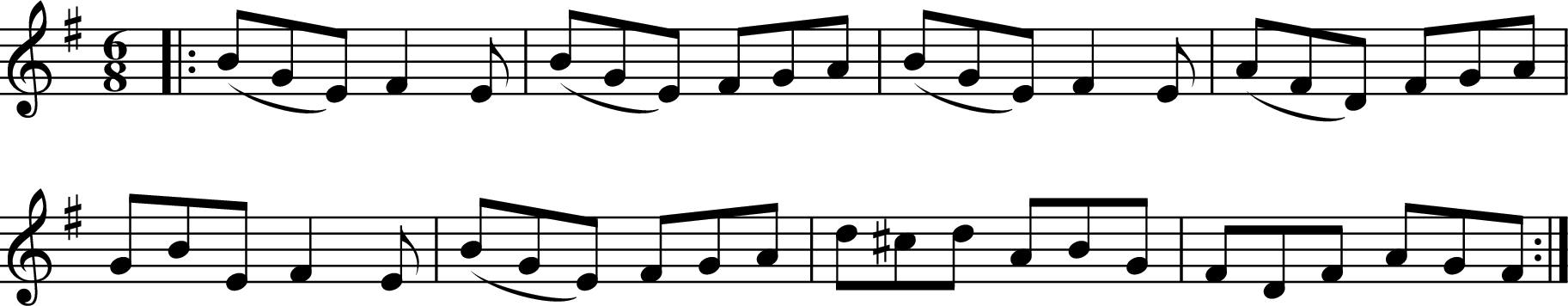

Arpeggios are another pattern that shows up all the time in melodies. An arpeggio is the notes of a chord played sequentially. The arpeggio of a C major triad contains the notes C, E, G, and the octave of C. The descending arpeggio has also been shown:

Arpeggio patterns are easy to recognise in music notation from the intervals they are built from: two sequential thirds, a line to an adjacent line, or a space to an adjacent space. They are found everywhere in music.

The tune The Monaghan Jig starts on a descending arpeggio with other examples following. I've marked them with slurs:

The Monaghan

Practising arpeggios and recognising their characteristic patterns in sheet music can be approached much like scales and intervals. An example exercise for the three-note arpeggios (triads) in C major can be seen below:

Inversions

Previously, an arpeggio was shown consisting of two sequential thirds, but it can also appear in another form called an 'inversion'. Arpeggios don't end at the octave boundary; the sequence 'C, E, G', for instance, can be repeated indefinitely through the octaves.

You can take a three-note slice from this, starting from any note; the resulting interval pattern will be different, but the notes will sound like the same chord if played together. If you took a three-note slice of the C major arpeggio starting at the E, you would get 'E, G, c', with the C at the top, which is called the first inversion. The second inversion is 'G, c, e'.

This is called an 'inversion' because another way to think about it is to take the root position arpeggio 'C, E, G', and invert it by taking the lowest note and putting it on the top, 'E, G, c'. The second inversion then repeats this process.

Inverted chords combine thirds (two staff positions) and fourths (three staff positions). When a chord is inverted, the 'name' of the chord is always the note at the top of the largest gap.

Inversions are often used as they allow a given chord tonality to be referenced by a melody, while allowing the notes to remain within a given range. An example of a second inversion of the A major arpeggio may be seen in bar 2 of Langstrom's Pony below.

An inversion allows the C and low E to ground the melody around the central note of A, with the repeated 'A' note emphasising that note within the chord.

Langstrom's Pony (fragment)

I'd recommend practising the inversions across your instrument's range for any scales you use frequently, in ascending and descending order.

Other common patterns

If you look at any sheet music, I'm sure that you will be able to find other repeated patterns with ease. Some of these will be common across many genres of music, while others will be found only in a single genre. Melodic figures are one thing that can differentiate one genre from another.

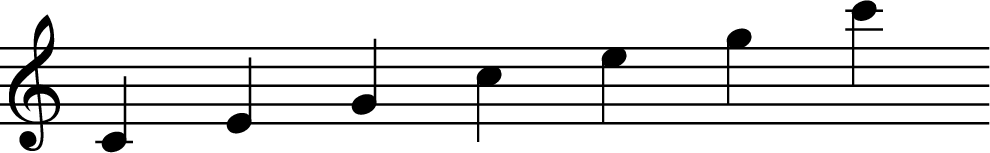

The patterns you see may include some of the ones shown below.

Another common figure is a second followed by a third, or a third followed by a second.

Both of these can be considered three-note 'slices' of different pentatonic scales, which is where the name comes from. However, they are often seen shifted up or down arbitrarily.

Any time you find a pattern repeated frequently in the music you play, it would be worthwhile isolating it and practising it across the range of your instrument.

Many other figures are discussed in the article Using melodic patterns to play by ear. Also, in 'The 24 universal melodic figures', which is my original source, numerous examples of their use in popular music are included.

Putting it into practice, recognising patterns in sheet music

Let's return to the first part of Jim Ward's Jig and recognise the patterns it uses.

- Following the starting G is an ascending scale run from G to B.

- There are many occurrences of the three-note pentatonic figure.

- Bars 5 and 6 are almost identical to 1 and 2, though 6 ends on an ascending scale run.

- Bar 7 includes a descending E minor arpeggio.

Once you start using figures, you'll recognise them everywhere in your music. Patterns can be recognised and performed from muscle memory, letting you learn new music and sight-read much more easily.