Utilising melodic patterns to play by ear

Something critical to realise about playing music by ear is that the notes found in melodies are not random. There are melodic patterns that show up over and over again, and learning to recognise these makes playing the ocarina by ear much easier.

The names I am using for some of these patterns were coined by music educator David Fuentes, who has a great article series giving examples of them in well-known music. You can find it linked at the end of the article.

What are melodic patterns?

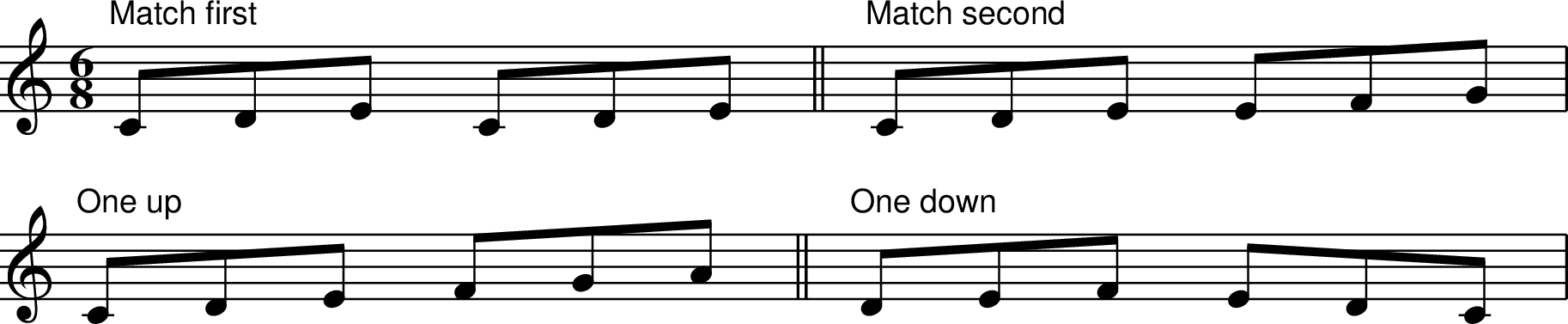

A melodic pattern, or melodic figure, is any short pattern of notes that occurs commonly in music. Take a look at the first part of the 'Swallowtail Jig' shown below, for instance. Can you see the repeating visual patterns?

You may notice several occurrences of a three-note 'slice' from a descending scale, shifted up and down in the range. This pattern is called a 'scale run', and examples can be found in most, if not all, genres of music.

Melodic figures are helpful because you can practice them over the whole range of your ocarina. The fingerings and breath changes required to perform the pattern become ingrained as muscle memory. This can be associated with the sound of the pattern, so that you know how to execute it as soon as you hear it.

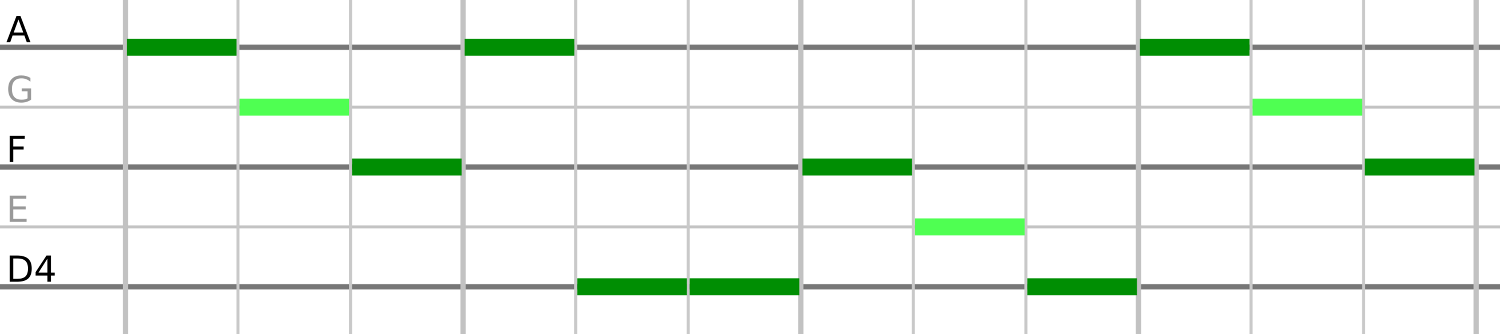

Let's see how it works in practice. The following is one octave of three-note scale runs for an alto C ocarina. Play through them repeatedly for a few days, until they can be performed from muscle memory without thinking:

Next, we associate this muscle memory with the audio, which involves considering how these patterns can fit together in music. For example, you may see two patterns that follow each other, where the second can start in different positions:

- On the same note as the first note of the previous figure.

- On the last note of the previous figure.

- On the note one step higher or lower than the last note of the previous figure.

To practice learning to hear and perform the figures in these relationships, you're going to need an assistant to perform them for you.

- Start by choosing two or three relationships, such as 'match first' and 'match last'.

- Practice playing the figures in these relationships on your instrument, and observe how they sound.

- Ask your assistant to play these for you. Listen to the whole performance, and perform what you hear. As additional guidance, your assistant can tell you what note the melody begins on.

For instance, one might start with something like this:

As you become comfortable with these, gradually introduce longer sequences of figures. Include the figures in different relationships and incorporate various figures, such as those found in the following sections of the article. All of these patterns can also be played to other rhythms.

You may find it helpful to look for examples of how figures are used in music to get some ideas.

Arpeggios

In addition to scale runs, another pattern that you will hear frequently in music is arpeggios, where the notes of a chord are played one after another. For instance, here is a C major arpeggio:

Arpeggios show up all over the place in music, including:

- 'Great Fairy's Fountain' from 'The Legend of Zelda'.

- The opening of the first movement of Beethoven's 'Moonlight Sonata'.

- The highland bagpipe tune 'Atholl Highlanders' also makes extensive use of arpeggios.

I'd suggest practising these figures in the same way as the three-note scale run, first learning to play them across the instrument's range.

The following are the arpeggios within the first octave of an alto C ocarina. Feel free to expand this to cover the full range of your ocarina, or start with a smaller section.

Then, once you have the basics, ask someone to create melodies that incorporate these patterns. It may be helpful to begin by contrasting the three-note scale run with a three-note arpeggio. You'll notice that the arpeggio has a more 'open' quality.

An arpeggio is defined as a specific pattern of three or more notes in ascending or descending order, comprising notes from a chord. However, arpeggios do not always appear in their native form. For example, while the melody of the 'Swallowtail Jig' shown earlier does not include arpeggios, its start is built on a framework of a D minor arpeggio.

The notes of this arpeggio are D, F, and A. Notice how the first and third note of the scale runs 'slot in' like building blocks in the places of the chord notes:

Most music is built on a chord progression, and it is common for the melody notes to align with the chord notes. This subject is explored in The relationship between melody and chords.

More melodic patterns

You now understand the essence of using melodic patterns to play by ear. From here, it's just a matter of gradually learning more patterns over time. The more patterns you know, the more often you'll recognise them in music as you listen.

There are hundreds of patterns which vary across musical genres, so here are a small selection to get you started. All of the patterns have been given in one position, but I'd suggest practising them over your instrument's range as shown previously.

Anticipating and resolving movement

The ascending or descending motion of a scale run or arpeggio in melodies is often emphasised by preceding it with a figure that initially moves in the opposite direction. For example, here is that idea used to emphasise an ascending scale:

There are many different figures that use contrasting movement in this way, but some common ones are the figures 'Crazy driver', 'Bounce', and 'Pounce' shown below:

Other figure patters can serve the opposite function, taking an ascending or descending movement, and resolving it to a single note. Some examples are two patterns called 'Little Holly Philip' and 'Plectrum'. These create a sense of resolution by surrounding the figures final note with a higher and lower note.

Arpeggio inversions

The notes of the arpeggio may also appear in different orders, which are called 'inversions'. Each progressive inversion is formed by taking the note of the bottom of the arpeggio and moving it up by an octave, until you get back to the root form of the arpeggio an octave higher.

Melodies often include inverted arpeggios because they allow different chords to appear within the same note range. For example, the first part of 'The Atholl Highlanders' transposed into C outlines the notes of a C major and F major arpeggio. If this melody used a root form triad for the F major section, the lowest note of the melody would suddenly jump up.

Ornamental patterns

Many kinds of melodic figures that one will hear are essentially ways of ornamenting simpler patterns, such as a scale run or a long note of one pitch. One of these is the auxiliary, where a long note of a single pitch is ornamented by playing note above or below in the middle of it:

It is also not uncommon to encounter patterns which oscillate between two adjacent notes, either notes from a scale or notes from an arpeggio:

A four-note scale run is often ornamented by reversing the order of the middle two notes, turning it into a pair of diatonic thirds. Both the scale run and double third figures start and end in the same place, but the second sounds more interesting.

Pedal notes

The final kind of melodic figure I want to mention is a sequence in which a melody repeatedly jumps to a given note, called a 'pedal note'. The term 'pedal note' comes from church organs, which have pedals to play sustained bass notes.

Pedal notes describe a general category of melodic figures, and a simple example is where a two-note scale run is ornamented by jumping up to the fifth of the chord:

Pedal notes are also found in longer sequences, repeatedly jumping to a lower or higher note, like the example below. An interesting phenomenon occurs if such a pattern is played at a high tempo; the mind merges the scale run with the jumps, and the fixed note is actually perceived in harmony.

There are many pedal note patterns in use in music, and because of that, I'd recommend identifying and learning the ones that show up often in the music you play.

Closing notes and further reading

Learning to recognise and play patterns by ear is helpful as it moves you from thinking about one note after another to one pattern after another. It's analogous to moving from sounding out one letter at a time to recognising whole words.

The patterns mentioned in this article are intended as an introduction and are by no means exhaustive. I'd strongly recommend reading the article ' The 24 universal melodic figures' by figuringoutmelody.com, which gives countless examples of figures in real music.

Also, try studying the music that you play regularly and see if you can identify any of these three- or four-note patterns for yourself. Common patterns do vary across musical genres.

You may have noticed that the sound of these patterns changes depending on where on the instrument you play them. We'll be addressing this next in Learning to identify melodic intervals by ear.