How to never think about your fingers again while playing the ocarina

I believe that many people struggle with playing the ocarina because they find it hard to get their fingers to do what they want. Yet, with the right approach, it is easy to get to a point where fingerings cease to be an obstacle to your playing.

In the article Practising the ocarina effectively, we discussed the idea of 'muscle memory'. For example, if you take your ocarina and repeatedly finger the note sequence G, B, A, G (assuming an alto C) to a steady tempo for several minutes, what happens?

At first, you may find that you need to think about the fingers you need to move for each note transition, but after a while, the movements start to happen by themselves. You'll be able to continue to perform the action while your mind wanders onto other things.

If you think about what you are physically doing while playing a song, you may realise that a song is simply a series of note transitions that follow one another.

But if you learn songs from start to finish, by practising the note transitions in the order they are used within this song, you may find that every new song you play feels like starting from scratch.

The problem stems from two things:

- First, by learning the whole song from start to finish, it gets stored in your memory as a single monolithic path. If you make a mistake, you'll likely be unable to continue and will have to start over.

- Second, the number of possible note transitions on only a single chamber ocarina, considering only the C scale, is quite large. Any single song will only make use of a small selection, so if you only practice songs, most of the instrument's possibility space will remain unlearned.

You can logically know how to finger two notes, but the physical act of moving between them may require thinking 'which fingers do I need to move', and this conscious act will cause stalling.

But what if you instead develop muscle memories for all possible note transitions, C to D, C to E, and so on, as individual units?

These could then be assembled in any order, like Lego bricks, allowing you to play music without needing to think about your fingers.

Internalising all possible note transitions in C major

Let's start by internalising all the note transitions in your ocarina's native major scale—C major for an alto C. The Idea here is to start from the low C in the scale, and then practice moving from this note to every other note on the instrument that's within this scale.

- C to D

- C to E

- C to F

- and so on.

I'd suggest starting by ensuring that you can play the notes of the C major scale, or the instrument's native major scale for ocarinas in other keys. For a multichambered ocarina, play the scale over the instrument's whole range.

I have omitted subhole notes from the shown exercise because practising the instrument's main notes will have the most obvious impact on improving your ability to play music.

If you find working with the whole range at once too challenging, feel free to break it into smaller slices. The following exercises can be learned on a small selection of notes, gradually expanding the range as your experience grows. This process is the same as demonstrated in the article Learning the ocarina's fingerings.

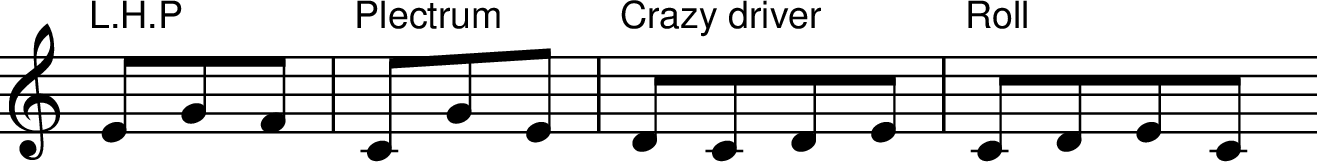

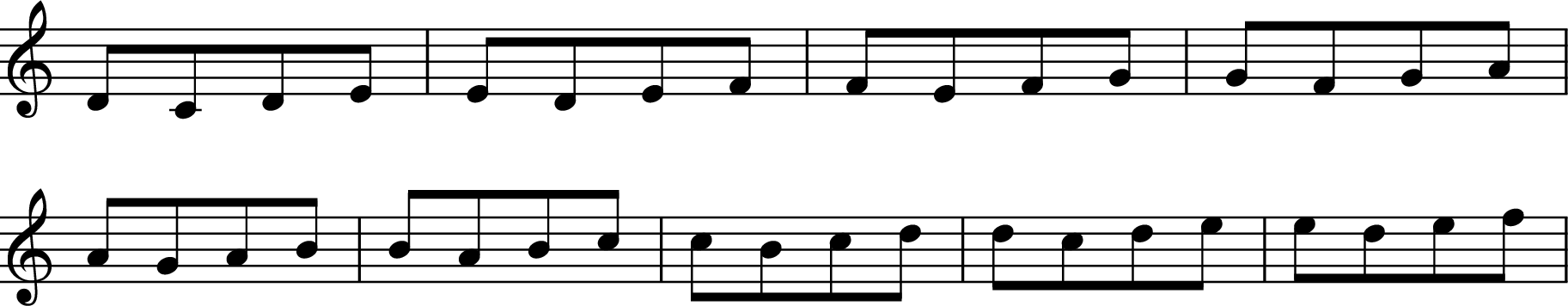

Once you can play the scale sequentially, start from the lowest note in the scale, and then practice playing a sequence of leaps starting from this note, to every other note on the instrument. Here is the pattern for a single chamber C ocarina (omitting subholes).

I'd recommend practising each of these transitions every day for a few days. You may wish to initially practice these without blowing the instrument and focus entirely on correct finger movements.

Some of these note transitions may feel easier than others, and it is probably the case that the easy ones have occurred within other music you've played. Something feeling awkward is often a symptom of unfamiliarity, rather than a physical or mechanical difficulty.

Playing leaps from low C to high D, E, and F of a single chamber C ocarina involves rolling your left index finger into a vertical position, while simultaneously rolling onto the tip of the right pinky, and rolling the right thumb. See Holding an ocarina on the high notes for some tips on performing large leaps.

Once you introduce blowing, articulate the notes with the tongue. I'd recommend using a chromatic tuner to check the blowing pressure needed to sound in tune, aiming to keep each note in tune over its whole duration. In doing so, you develop muscle memory for the breath pressure required as well as the fingering, which will help you play in tune consistently.

Using a metronome to pace yourself can help, as pushing yourself to play too fast may feel overwhelming. Start at a low tempo, and then gradually work up the speed. Keep practising for a few minutes every day until you can play at about 120 bpm without actively thinking about your fingers. This may take several weeks.

Learning the transitions from D

Then the next step is to take this same idea and repeat it beginning from D:

- D to C

- D to D

- D to E

- and so on.

Then from E, F, G …

Then repeat the same pattern starting from E, F, G and so on, until you have played the transitions from every note in the instrument's native major scale, to every other note.

If you keep practising this every day for a few weeks, you'll reach a point where you don't need to think about which fingers you need to move to make the transition, it 'just happens'. Once you have this muscle memory in place, you'll notice a few things:

- First, learning new music in C major will be much easier.

- Second, it will be much easier to develop skills like sight-reading notation, playing by ear, or performing music that you have in your head.

By moving the task of finger movements and breath changes into the subconscious mind, you are free to think about the stylistic aspects of your performance instead. It also enables you to play more complex and higher-tempo music, which would overwhelm the conscious mind.

Many music-learning resources share simple exercises like this. Still, very few offer insights into the direct correlation between their practice and the enhancement of one's ability to perform the music they want to play. Thus, the exercises can seem like tedious, senseless work. It should now be clear why this isn't the case.

The exercise outlined here may be the most efficient way to create the muscle memory required to internalise the instrument. It exhaustively covers every finger transition that is possible on the instrument (within one scale), with each one performed exactly once.

If you only ever play songs, there is no guarantee that you'll even use every transition, regardless of how long you practice. Some intervals will unavoidably occur more often than others, leading to the development of an uneven skill set.

Learning the finger and breath transitions for other scales

Once you can play the note transitions within the C scale (or the native scale of your ocarina for instruments in other keys), you may move on to practising the note transitions for different scales. Let's consider F major, for instance.

As before, I recommend starting by learning to play the scale across the entire range of the instrument. While in C major the fingerings follow a logical linear pattern, the other scales use cross fingerings that follow an irregular pattern. By practising moving through the notes of a scale sequentially, you build a linear muscle memory for the fingering sequence, and can perform the scale without being aware of the irregularities—your subconscious hides them.

When the tonic note of the scale you are playing starts somewhere in the middle of the range, I'd suggest playing from the lowest tonic note upwards to the highest scale note that you have on your instrument. From there, return down to the lowest note, and then back up to where you started. Include subhole notes if you wish.

Feel free to break this down into smaller slices as previously discussed if you find the entire scale or interval pattern too much to handle at once. Also, Pure Ocarinas has a Scale generator tool which can generate these exercises for all the possible scales, for many kinds of ocarina.

Once you can play through the whole scale linearly, start practising navigating the same scale in leaps. For scales where the tonic is in the middle of the range, one way to approach it is to leap from the starting note to the lower notes first, then to the higher ones.

Organisation and prioritisation

You may have realised that there are many of these patterns possible, even within the range of a single chambered ocarina. It helps to prioritise them, and there are a few ways of doing so:

- Learn the note transitions in scales that you use frequently. For example, if you often play music in B flat, then practising the note transitions in B flat would be beneficial.

- Learn them in circle of fifths order. The circle of fifths organises keys by the number of accidentals, and for a C ocarina would give you: C, G, F, D, B♭, A, E♭, E, A♭, B, D♭, G♭. This is the order music curricula typically teach them.

Pacing your learning is one place where having a teacher can be very helpful.

As you start learning scales with more accidentals, you may find that it helps to learn to play the intervals within your ocarina's chromatic scale, literally every possible note transition that exists on the instrument. For example, here is every chromatic transition from low C:

Learning these may save time because it prepares you with the muscle memory for how to move between different notes. Learning the other scales then becomes a task of developing the muscle memory for the sequence of fingerings, not learning the muscle memory to move between two notes from scratch.

Arpeggios, intervals and melodic figures

By practising these two note transitions in isolation, you're developing muscle memory that associates these two notes. This then makes things like reading music notation, playing by ear, and on-the-spot improvisation easier. But why stop at two note sequences?

There are many multiple-note patterns that occur throughout different kinds of music. If you get all of them into muscle memory, you have the same advantage: when you encounter them in the music you are playing, you just perform the pattern 'as a whole' instead of needing to think about it one note at a time.

Arpeggios

Music consists of layers. Ocarina players are most often concerned with the layer of melody, but underneath most melodies, there is harmony (think of someone strumming a guitar). Harmony is based around something called a 'chord', which is a selection of three or more notes. These notes may be played at the same time or sequentially, the latter being called an 'arpeggio'.

Simple chords are based on an interval (the distance between notes in a scale) called a 'third'. It is the distance where you choose a note in a diatonic scale like C major or D major, and skip forwards by two notes.

Intervals can be stacked, and a common type of chord is formed from two sequential thirds. If you start in C major on the note C, moving forward by one third gives you the note E, and a second third gives you G. Taken together, these give you the triad: C E G. The notes of a triad repeat indefinitely in higher and lower octaves.

While a guitarist or pianist may play the notes of a chord simultaneously, in melodies, these notes are often played sequentially. On a single chambered C ocarina, it is possible to play one full arpeggio of C in the low octave, and two notes of the second octave.

Because arpeggios occur so commonly in music, it is well worth practising them until they enter your muscle memory. For C major, these are the arpeggios you'd want to practice.

- C Major

- D Minor

- E Minor

- F Major

- G Major

- A Minor

- B Diminished

Notation for these can be found in The essential arpeggios for ocarina. There is much more information about harmony and arpeggios in the article Harmony for ocarina players.

Diatonic intervals

Another pattern that is often encountered in music is a sequence of two intervals, for example, a sequence of two diatonic thirds, in either ascending or descending order:

It is easy to get these sequences into your muscle memory from every note on an instrument by practising all the sequential intervals in ascending and descending order. The thirds within the C scale sound like this:

For scales that begin in the middle of the range, the intervals can be practised by ascending from this note to the highest interval possible in the range, and then playing an interval sequence descending to the lowest note, before ascending to the note you started from.

Here are the thirds within the G major scale, for a single chambered C ocarina:

The other intervals within the scale can be practised in the same way. For example, to practice the diatonic fourths, you'd play a sequence formed from moving forward by three notes, and then down by two notes. Pure Ocarinas has an Interval generator tool, which can create these exercises for any interval size, scale, and ocarina range.

Melodic figures

A melodic figure is a short sequence of notes, often three or four notes long, that forms an individual melodic 'unit', a 'melody word' in a sense. The three-note arpeggio and the four-note 'double interval' discussed previously are two examples of figures, but there are many more common patterns found in music.

The following patterns, for example, were found (and named) by a music researcher called David Fuentes. David has studied the patterns that occur in many different kinds of music and created a taxonomy of the most commonly occurring ones.

Figures are often easy to identify within sheet music, and a given genre of music will commonly include many similar figures. It can be worthwhile practising those figures across your instrument's range. Starting from every note in a given scale, play the figure you want to practice, omitting the ones where the figure would go out of range.

For instance, here is how you can practice the figure 'Crazy driver' over the full range of an alto C ocarina (omitting subhole notes):

Etudes

The term 'etude' literally means 'study' or 'exercise', and everything we have been practising so far is a kind of etude. Probably more widely known, though, are etudes which are technical exercises, composed in a musically interesting way.

With regard to initially developing the muscle memory to move between all the notes on an instrument easily, my feeling is that practising musical etudes will be less efficient than practising simple note leaps, unless the etudes have been composed carefully to make use of every note transition on the instrument, and use them relatively uniformly.

Where etudes come into their own is to develop deep familiarity with larger-scale melodic figures and patterns that occur throughout many kinds of music. The method book 'The Mezzetti Ocarina Tutor' includes many etudes for the ocarina, and Giorgio Pacchioni also has numerous ocarina etudes available on his website.

Closing notes, ornaments, microtones and other considerations

Through this article, we've explored some simple exercises that allow you to rapidly develop the muscle memory required to move around the notes on the ocarina, eliminating the need to think about your finger movements or breath pressures.

While we have been working only the major scale, the same ideas can be easily applied to other scales, like minor scales or blues scales. In fact, it is also easy to extend this to any scale you like, including pentatonic ones.

You could also include alternate fingerings if you find them valuable in your playing. In which case, you'd practice the note leaps for a scale in the same way, but instead of performing only one fingering per note, you'd leap to the same note two or more times, executing each of the alternative fingerings you'd like to practice.

The discussed approach can even be used to practice microtonal intervals like quarter tones, where each octave is split into 24 tones instead of the usual 12. These pitches can be attained on a standard transverse ocarina through partial hole covering and varying blowing pressure. Exhaustive practice could be used to develop the skill to perform them consistently.

Practising all of these would take a considerable amount of time. What I'd recommend is to keep the ideas in your tool set and practice things as needed, when you find that your fingerings are hindering you.