Notating fingered articulations (cuts and strikes) in ocarina music

As discussed in a previous article, fingered articulations are an approach to separating notes by sounding a higher or lower pitch for a brief duration.

These techniques originate in folk tradition where their usage and application is an aspect of playing style. Sheet music provides only the notes of a tune, and then individual players apply fingered articulations in their own way. This is learned by ear through the imitation of performances.

Due to these factors there is no universal, unambiguous way of notating fingered articulations. Several approaches exist, many invented by authors of written learning resources. These systems vary a lot in their clarity.

Grey Larsen notation

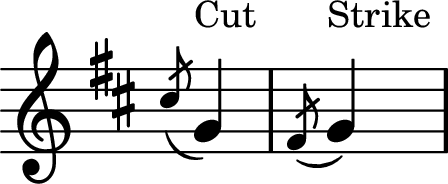

In his book 'The Essential Guide to Irish Flute and Tin Whistle', Grey introduces a system whereby cuts and strikes are notated using symbols placed above notes.

- Cuts are notated by placing a blocky comma ',' directly above the note.

- Strikes are notated by placing an arrow above a note.

In case these symbols are unavailable in notation software, the same intent can be communicated using textual annotations: 'CT' means 'cut', and 'ST' means 'strike'.

This is my preferred notation system because I find clearly communicates intent. It is less verbose than the other options mentioned below, and is conceptually similar to other articulation notations like staccato dots. I find it easy to read.

It does have a few limitations, including that it does not indicate which finger should be used to perform the articulation. In most cases this does not matter as a correctly performed cut or strike is so brief, its pitch is not perceived, and so any fingering can be used, depending on what is easiest.

If one needs to indicate a fingering in a teaching resource, this can be explained with prose, or one could use numbers to indicate the cutting or striking finger, in a similar way to fingering notation for piano.

Visual ambiguity may exists in that the wedge symbol of the cut is similar to a breath mark, but can be easily avoided using a visually different breath mark. The down arrow is visually similar to an up bow mark used in string instrument notation, but I don't think this would matter.

Notations using grace notes in folk music

Fingered articulations are in widespread use within Irish and other folk music traditions of the British isles. The authors of books teaching the tin whistle, flute, folk fiddle and similar instruments have come up with systems for notating fingered articulations using classical grace note symbols.

Grace notes are small note symbols written before another note, and two kinds of them exist in classical theory:

- Appoggiatura, which typically notate optional melodic details.

- Acciaccatura, written with a slash and intended to be played 'as fast as possible' before the note they are ornamenting. Typically using 'correct' fingerings.

The general idea behind these notation systems is that a grace note placed above the parent note means that it should be articulated with a cut, and a grace note placed below means that it should be articulated with a strike.

Beyond this, the notation is inconsistent. Many examples do not differentiate between acciaccatura and appoggiatura, and I would recommend treating any singular grace note that you encounter in a notated folk tune to mean 'play a cut' or 'play a strike', irrespective of its written duration.

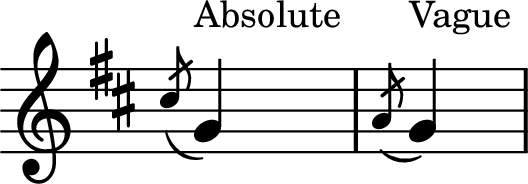

The placement of the grace notes head sometimes indicates the finger that one should use to perform the cut or strike. In other cases, its absolute position does not matter:

- Absolute notation uses grace notes to represent the finger a cut and strike should be performed on. The example of absolute notation below is for a D tin whistle and means "play a cut using the 'C' finger" (the left index finger).

- Vague notation places a grace note on the line above or below, and just means 'play a cut' or 'play a strike' like Grey Larsen's notation. It does not mean 'play a cut on the next scale degree'.

These terms reflect patterns that I've observed in real music notation, and are not in common use.

On the ocarina I'd just treat both kinds of notation as vague and use whatever fingering is easiest. On a tubular instrument cutting higher up the tube produces a higher pitch. Because of acoustic differences between tubular and globular instruments the fingerings don't translate well.

Strikes in both absolute and vague notation are represented by placing a grace note on the scale degree below the current note. This is due to a limitation of the tin whistle and similar instruments, as it is only possible to strike the hole below the lowest open hole.

You may also run across instances where multiple grace notes occur before a note. These are typically attempts to notate rolls and cranns.

Unfortunately, this notation often doesn't bare much resemblance to how they are played. For instance the example below shows a group of grace notes interpreted as an Irish long roll, but there are other ways one could interpret it.

Exploring all of the variations of these grace note blocks and how it should be performed is beyond the scope of this article. Numerous variations exist having been made up by different authors, and many of them are attempting to notate the same intended performance.

These groups of grace notes are quite meaningless without additional information, and I dislike this kind of notation because it does not clearly communicate to the performer what they should do. It is preferable to just notate the individual cuts and strikes, as in the expanded example above.

I'd recommend the book 'The Essential Guide to Irish Flute and Tin Whistle' if you want to learn more about the ornamentation used in Irish music. It is a comprehensive study and is easily adapted to the ocarina.

Highland bagpipe notation

The Highland bagpipe also has a comprehensive system for notating fingered articulations. The instrument was adopted by the army in the 1800's and played in large pipe bands. Standardised notation was developed to coordinate the group.

The Highland bagpipe is an instrument of its own, deviating from classical theory in several ways. The scale runs from G4 to A5 with two sharps and is not chromatic. This may be considered an A Mixolydian scale or several modes of D. The instrument's sounding pitch is typically higher than written, but varies between instruments.

In a bagpipe the player blows into a bag which acts as an air reservoir, and pressure is regulated by squeezing the bag. Air constantly flows from the bag through several reed pipes, including the 'chanter', the melody pipe, and one or more drones that play a fixed accompanying pitch.

Air constantly flows from the bag, through the pipes, and it is not possible to 'tongue' notes as on other instruments. Early players of these instruments noticed that an impression of separate notes could be achieved using extremely short 'notes', so brief as to sound like a 'click'. They started using this approach to articulate notes, using special fingerings to make this easier.

Highland bagpipe notation represents these fingered articulations using grace note symbols like folk musicians sometimes do. As far as I can see, the notation does not interpret them in the same way as classical theory. Appoggiatura are used exclusively, and how they should be performed depends on context.

A single grace note represents an articulation. They are meant to be played with a subliminal duration and are placed exactly on the beat or sub-beat of their parent note. In order to achieve that reliably, special fingerings are used, lifting or striking a single finger.

They are interpreted quite literally. A grace note on G means to very briefly uncover the G finger hole (play a cut using the G finger).

Highland bagpipe notation also makes use of groups of two or more grace notes beamed together. These groups correspond to one of a set of standardised embellishments, including throws, grips, or doublings.

Unlike singular grace notes, these groups do not tell you exactly how to perform the embellishment, and the relationship between the notes and the intended performance is quite inconsistent.

The notation below shows approximately how a 'grip' is performed. This embellishment is performed before the note it is embellishing. The two low G's are performed with 'proper' fingering and are normally perceived as notes. The C grace note is performed as a cut by briefly opening only 'C' finger.

Many highland bagpipe ornaments jump to low G like this, as it is the loudest note on the instrument. Leaping to the low G serves as a means of creating emphasis.

The next example slows another kind of embellishment called a doubling, a double articulation of a single note. Rhythmically, it begins in time with the embelished note, and is performed as two cuts. The first cut is played on the beat of the embellished note and the second marginally later.

As you can see the notation isn't consistent. Some of the grace notes are played as cuts or strikes, by opening or closing only a single hole, while others are played with 'proper' fingerings, requiring opening or closing multiple holes.

Rhythmic interpretation is also inconsistent, as even though the grace notes written have the same duration, some are played longer than others. In some cases the embellishment as a whole precedes the embellished note, while in other cases it follows it.

This inconsistency and lack of a literal interpretation doesn't matter within the highland bagpipe tradition because players are taught through a teacher demonstrating the correct performance to a student at a low tempo. They learn to associate the visual pattern of the notation with the performance, much like a guitarist can associate a chord symbol like 'C', with a given fingering pattern.

Approaching the study of bagpipe notation I did for this article, I had expected the notation would more clearly indicate how something is to be performed and was surprised to find that it doesn't.

This ambiguity could be reduced quite easily if the notation were to use acciaccatura exclusively to represent cuts / strikes, then use appoggiatura to notate notes that are held for a perceptible duration, the meaning of groups of grace notes would be less ambiguous.

Without this, I find it interesting that Highland pipe playing still remains very dependent on oral tradition.

Why using grace notes for notating fingered articulations could be ambiguous in ocarina music

In contrast with the highland bagpipe and folk traditions, the ocarina player community is less insular. Most skilled ocarina players did not start on the instrument, but came to it having learned another instrument previously. The ocarina has players from many backgrounds, including folk musicians, and those with classical training.

The usage of grace notes for notating fingered articulations can be ambiguous because it deviates from what they are taught to mean in classical tradition. Of the two kinds of grace note symbol, acciaccatura are closest in concept to fingered articulations, since they are intended to be played 'as fast as possible', but there remains an ambiguity between weather one should be using correct or false fingerings, as well as the exact rhythmic timing (before the beat or on the beat).

Folk fiddle techique does differentiate between grace notes and cuts. Grace notes are performed by fully depressing a string to the fingerboard to sound the note, while cuts are performed by flicking a finger across a string, barely touching it, and serving to briefly mute the string.

It is also apparent if you study guides on playing the instrument, that Highland pipe players do make a distinction between ornamental grace notes and fingered articulations, even though they don't have a word for it.

The alternative way of using and interpreting grace notes works for the Highland pipe community as it is deeply ingrained in the instrument's tradition. Players learn what they are and how to perform them while learning the instrument.

But with the ocarina, It would not surprise me if some players already use grace notes under the assumption of their standard interpretation in classical theory. Also using them to notate fingered articulations could be ambiguous. Using a distinct notation like Grey Larsen's avoids that.

It is also worth considering how naming can impact understandability. Calling cuts and strikes 'grace notes' can be confusing as people have a preconceived idea about what a 'note' is, and fingered articulations do not serve the same function, and are not perceived the same.

Closing

Understanding how cuts and strikes are notated within the music traditions that use them allows you to interpret this notation as it was intended.

For notation that you are using yourself, you can do whatever you want. But when sharing or publishing music, more care is needed. I'd suggest using Grey Larsen's notation or something semantically equivalent to avoid ambiguity.

If you use grace notes to notate fingered articulations in published ocarina music, I strongly recommend including a description of how to interpret and play them since this may be ambiguous out of context.

References

- The Piper's Corner: Understanding Bagpipe Music (web page).

- Learning the Great Highland Bagpipes (Ian B Ferguson)

- Learn to play the Highland Bagpipe (Andreas Hambsch)

- Numerous demonstrations of highland pipe embellishments on YouTube.

- The Essential Guide to Irish Flute and Tin Whistle (Grey Larsen)

- Mel Bay's Complete Irish Fiddle Player (Peter Cooper)