Developing your sight-reading on the ocarina

Sight-reading is the ability to play any sheet music you see at first sight. That means to be able to look at some notation that is new to you and instinctively know what to do to perform it.

It's possible that you've tried this before and that the goal felt unachievable. However, I think the difficulties people encounter are caused by traditional teaching methods.

Reading music has mostly been taught to happen in a conscious and analytical way, by recognising note positions, decoding them to note letters, and figuring out rhythms by consciously counting them. These tasks place a significant burden on the conscious mind.

Sight-reading is considerably easier when you instead practice in a way that makes the process completely subconscious.

There are two key steps in reading music: first, you need to be able to recognise what the notation is telling you to do, and second, you need to be able to perform that on your instrument.

It is pretty straightforward to automate those tasks using muscle memory and visual pattern recognition. The previous articles in this section have already been guiding you along that path:

- Develop muscle memory for every possible finger transition.

- Learn to audiate rhythm notation.

- How to associate the visual patterns of notation with their equivalent muscle memory on the instrument.

If you have followed through with these, you are already well on your way to becoming a competent sight reader. Developing your skill from there entails finding out what you can and can't read, as well as practising the things you find difficult.

Finding and working with your limit

Everyone has a limit to the complexity of notation they can sight-read. To improve your proficiency in this skill, it is essential to know this limit because practising with music that is too easy won't lead to meaningful progress, but things that are too hard will be overwhelming and feel intractable.

Finding your limit

The process of reading sheet music is, in many ways, similar to reading English. While reading English, your subconscious mind recognises the visual patterns of words and pronounces them to you. Likewise, when reading music, your subconscious identifies melodic and rhythmic figures within the notation and associates them with the equivalent muscle memory on the instrument.

Your ability to read English is constrained by the number of words that you know, so your ability to read music is the same as asking, 'What patterns have I internalised?'

It is straightforward to answer that question by attempting to read a variety of music and noticing what causes you to stall. One option is to simply get a large amount of sheet music of varying complexity and make notes about the things that you can and can't read.

It is also possible to explore your reading limit using a systematic approach. The idea is to start by writing out some simple music, and then gradually create more complex examples.

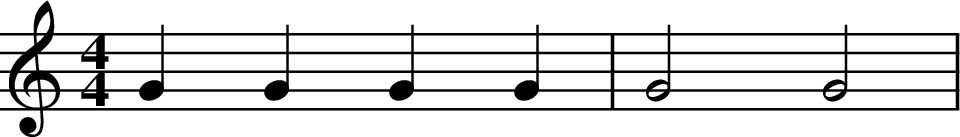

To begin, write out a simple example on manuscript paper. Use one pitch, with rhythms using only quarter notes and half notes. Can you read through this from start to finish at a steady tempo without errors?

If you can read this easily, that's great. If not, it just means that you've found your limit and need to spend some more time practising at this level. More exercises can be created easily by taking the same notes and writing them in different orders.

Once reading a given exercise becomes easy, the next step is to make the notation progressively more complex, which can be done as follows:

Increase the variation in rhythmic patterns

Music with less variety in its rhythmic patterns is easier to read, and more varied music is harder to read. You could start with something using only a few types of notes, then introduce shorter or longer notes, rests, ties, syncopations, tuplets, and other time signatures.

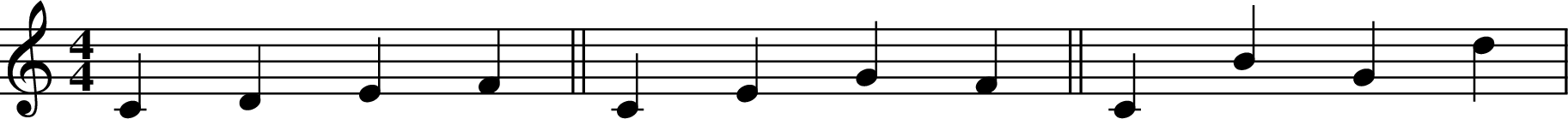

Increase the range of pitches

Music is easier to read if it only has a range of two or three distinct notes, and more challenging if it spans a broader range of notes. Possibly start with a range of two or three notes and gradually increase the range by introducing one more note at a time.

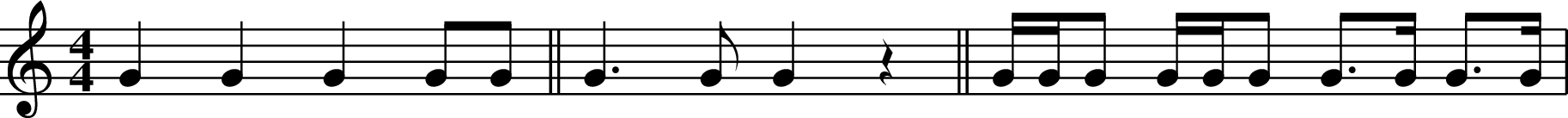

Use larger intervals

Notation that just moves between adjacent notes (such as C to D) is easier to read than notation that moves by larger leaps. Gradually introducing larger intervals is one way of controllably raising the difficulty of reading.

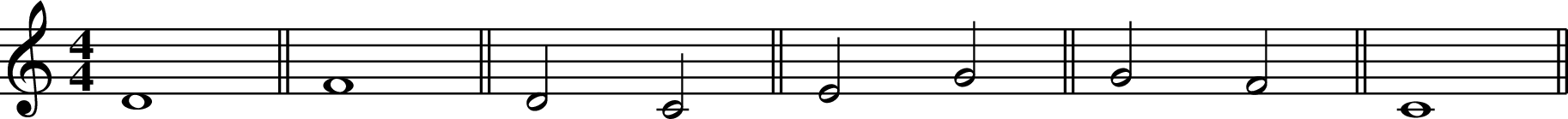

In the example below, the left case uses only seconds, and larger intervals are included towards the right.

And more

- Introduce other key signatures.

- Introduce accidentals.

- Introduce other time signatures.

- Change the time signature and/or key signature in the body of the music.

I'd recommend varying only one of the factors mentioned above at a time, such as range or rhythmic complexity. As you do so, take note of what things you can and can't read easily. There are many examples of how these things vary in real music.

Working with your limit

By following through with this process, you'll get an idea of the things that you can and can't read. For instance, you may find that:

- You can read music that uses small intervals without difficulty, but music that includes large leaps causes you to trip.

- Possibly, you find that rhythms including tuplets or sixteenth notes cause you to trip.

Improving your sight-reading is a matter of practising the things that cause you trouble one at a time. Is it a rhythmic or melodic pattern that you have difficulties with, or possibly both? In either case, it can be made into a figure and practised by itself.

As noted, music reading is a two-step process of recognising what the notation is telling you to do and having the muscle memory to perform that on your instrument. You may also find it helpful to consider which step is causing you trouble.

Say that you are struggling with a rhythm pattern. Is that because you are struggling to recognise the patterns in the notation, or do you need to stop and think, 'What does this rhythm sound like?'

- Issues relating to knowledge of what a rhythm sounds like can be addressed by spending more time listening and clapping the figures of that rhythm, until it is automated by audiation and muscle memory.

- Likewise, issues related to fingering can be addressed by practising the problematic finger transitions until automated by muscle memory.

- Issues related to recognising the visual patterns in notation can be addressed by reading more notation that uses those patterns.

Reading ahead

When you read something from notation, it is not necessary to immediately play it on your instrument. Instead, you can hold it as an instruction in your memory, leaving you free to play it when you wish. The skill of reading ahead helps a lot with achieving smooth sight-reading because it gives you much more time to process the upcoming notation.

When you are reading and immediately performing, you need to be able to process the notation and connect that to what you need to do on the instrument in a tiny fraction of a second. By reading ahead, you decouple those processes, allowing you to read what you are going to play next while your subconscious is playing the previously read notes.

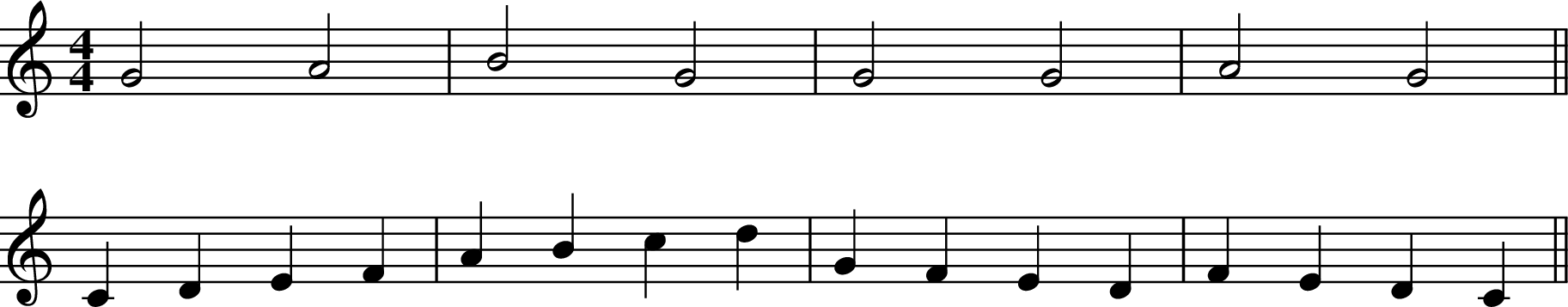

A good way to begin developing this skill is to start practising reading and remembering chunks of notes, without worrying about maintaining the rhythm between chunks. Write out some simple notation like the example below. I'd suggest making the first part have only one note per bar.

Then:

- Take a look at the first bar and notice what note it is telling you to play.

- Without naming the note, imagine how you would perform it on your instrument, but do not do so yet.

- Look away from the notation, and play the note, holding it for the specified duration.

Repeat that process for the other bars in the music. When there are multiple notes in the bar, remember all of them, think how you would perform them on your instrument, then look away and play them.

See the article Utilising common patterns in sheet music if you need some help with doing so.

Reading ahead in real time

Once you are able to read chunks of music and look away before performing them, try playing each chunk you read at the correct rhythmic time:

- Take a look at the music and remember as many notes as you can.

- Start playing these notes.

- While you are playing and before you run out of notes to play, look forward to the notes that you are about to play.

Begin by using simple notation and gradually increase the complexity over time. You may need to spend a few days or weeks on the first step (memorising and looking away) before doing it in real time becomes possible.

As previously mentioned, practising melodic figures and other common sequences will help because it allows your subconscious to perform a sequence of notes as a unit, removing the need for you to process the notation 'one note at a time'.

Finding and making exercises

One of the challenges of learning to sight-read is the need for a lot of notation. Each piece can only be used a few times before you start to memorise it, at which point you won't be reading any more.

On top of that, the notation needs to be organised by what rhythmic and melodic figures it makes use of, so you can find things relevant to what you are trying to practice, which also doesn't overwhelm you.

There are a few options:

- Crafted exercises. There are books of hand-crafted exercises and real-world music that have been arranged by difficulty, for ocarina and similar instruments. This is also the role that many 'method books' try to fill.

- Compose! Get some manuscript paper and make your own exercises. If you have a friend learning with you, creating exercises to challenge each other can be a fun way to learn.

- Random generation. There are tools online that generate random sheet music. They let you specify the key, range, and rhythms to use. It may not sound very musical, but it's a great way to create a large number of exercises with low effort.

A challenge that arises from pre-crafted exercises and linear method books is that they are impossible to balance to the needs of all learners. Different people will find different things more or less challenging and need to spend significantly more time on some tasks than others.

This is not a problem, and is not an indicator of ability. However, should you find that something is a sticking point and you need more exercises, using pre-crafted exercises as a basis to create additional exercises is an option. Use the patterns in the rhythms and melodies, reorder them, and change the pitches.

Developing your reading speed

When you're new to sight-reading, you may find that it takes a long time to process the notation, leading you to be able to read music only at a low tempo. This is normal, and you'll find that your tempo naturally increases with experience.

If you would like to practice this deliberately, it can be done like this:

- Use a metronome, starting initially at a low tempo, and read music in time with it. Gradually increase the tempo until you begin to make mistakes.

- Slow down the metronome a bit, and practice reading music of similar complexity at this tempo for a while, changing the music regularly.

- Increase the tempo by 5 to 10 BPM, and keep reading music.

By doing this regularly, your reading speed will gradually improve.

Closing

Learning to sight-read is a process of developing muscle memory for all of the note transitions on your instrument and learning to audiate various rhythms. Then you create a subconscious association between those things and visual patterns used to represent them in notation.

By paying attention to what you can and can't read easily, you may practice your weak points to improve over time. And by learning to read ahead, your playing will become smoother.

This process pays off big time in the long term, as you will be able to effortlessly play any music you encounter that fits in the range of your ocarina. Stick with it, and before long, you'll be easily reading notation you thought was impossible.