Sharps, flats, and key signatures

As we explored in the article Playing the ocarina with sheet music, sheet music notates the seven natural notes of the octave, called:

A, B, C, D, E, F, and G

But don't we have 12 notes per octave? As explored in Octaves and scale formation, most music uses only seven of the total 12 notes at a time, and the other notes are represented in relation to these using accidentals (sharps, flats and naturals).

Sheet music follows this same convention, but there are some important considerations regarding how these symbols are used and the context in which they apply.

Accidentals (sharps, flats, and naturals)

A sharp sign (♯) simply means to play the note one semitone higher within the chromatic scale. It is placed before a note and remains in effect until the following bar line.

Likewise, a flat sign (♭) does the opposite, telling you to play the note one semitone lower:

Finally, there is the natural symbol (♮), which undoes the effect of any previous sharp or flat, returning the note to its 'natural' state.

The notes shown above correspond directly to notes on your ocarina, and you can find out how to play them by looking at your fingering chart.

Note that multiple sharp or flat signs on the same staff position are not additive. If two C notes are marked sharp within one bar, both refer to the same C sharp on your instrument.

Accidentals used within the body of a piece of music:

- Remain in effect until the next bar line.

- Only affect the pitch of the line or space they are on. For instance, sharpening low D does not affect the D an octave higher.

- Can be cancelled within the bar using a natural sign before a note.

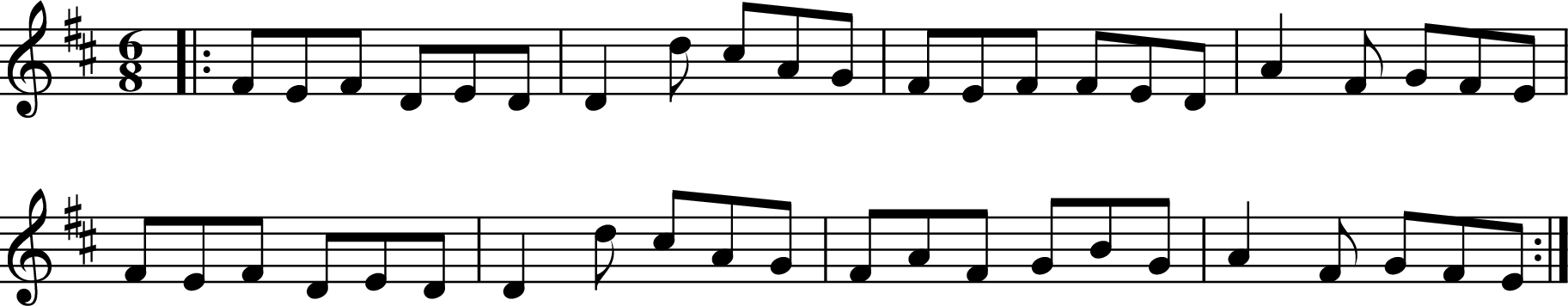

Using accidentals, music in any key can be notated. For example, we can notate music in D like this:

Introducing the key signature

With accidentals, we can notate music in any key. However, do you notice how cluttered the example above appears? Key signatures solve that problem, specifying the notes that will be sharp or flat within an entire piece of music (or until the key signature is changed). They are written by placing one or more sharp or flat signs at the start of each line, like this:

Using this key signature, the previous tune can be written as shown below. Notice how clean it looks without the scattered accidentals.

Unlike accidentals in the body of music, the accidentals in a key signature affect all notes of the same name in all octaves. That means, while only the top line F has a sharp sign, all F notes should be played as F sharp. The same is also true for the C sharp.

The order and placement of the sharp or flat symbols in a key signature are standardised, and because of this, it is possible to know what scale some music is written in at a glance. There is no need to remember all of the key signatures, though, as that will come naturally with experience. However, being aware of their existence is important.

The common key signatures

You can see all of the common key signatures below, organised into increasing numbers of sharps and flats. This diagram is called the circle of fifths. It is organised with C major (no accidentals) at the top, the sharp keys on the right, and the flat keys on the left. As you go down either side from the top, the number of sharps or flats progressively increases.

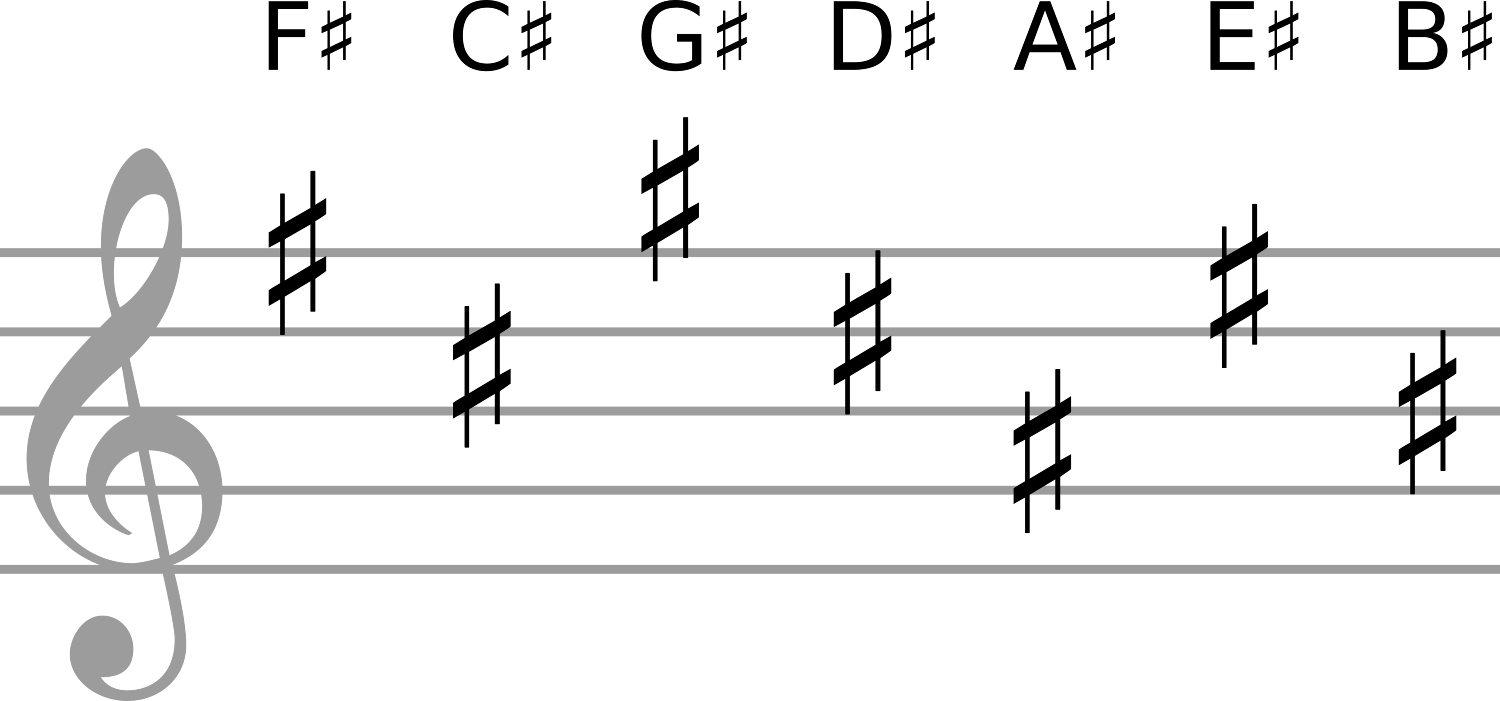

The sharps and flats used in these standard key signatures are always in the order and positions shown below. You could cover one of the two diagrams on your screen with our hand, and slowly slide it to the right, uncovering the accidentals one after another, noticing how the sequence matches the one in the circle of fifths above.

How to play music with a key signature

Playing sheet music with a key signature on the ocarina is as simple as substituting the marked notes for their sharp or flat equivalent, as indicated.

You can do this consciously, reading the key signature, noticing which notes are marked as sharp or flat, and substituting them. However, it's a much better idea to make this process subconscious. Thinking about fingerings is slow and may cause you to stall. It can be approached as follows:

Step 1: Learn how to finger all of the notes in the key

Say you wanted to learn to play music in the key of B flat on an alto C ocarina. I would advise learning to play the scale and all of the note transitions within it so that you can move around within the scale without thinking about how to do so. See How to never think about your fingers again while playing the ocarina.

Besides C major and its modes, all of the scales require cross fingerings and don't follow the same regular pattern of 'lift or place one finger sequentially to get the next note in the scale'. However, by practising the fingerings in the scale sequence, the irregularities become muscle memory, enabling you to move around in the scale with the same ease as if it were following a regular pattern.

Keys with more accidentals are not objectively more complex to learn; it is just a matter of breaking things down and practising the fingerings until they become automatic.

Step 2: Practice reading sheet music in this key signature

Once you can comfortably navigate the scale, I'd recommend playing a range of music and exercises in this key until you can read comfortably. Here is a tune that you could use to get started. Technically, it's in G minor, but the key signature is the same as B flat.

En Avant Blonde in G minor

The order of learning key signatures

Depending on what you're looking to achieve, there are three ways that you could order your learning of the key signatures:

- Learn the ones you need to play the music you want.

- Learn to play them in order of increasing sharps and flats.

- Learn the ones you need, then learn the others later.

The first option works well if you intend to play only a few tunes/songs alone. However, it could pose problems if you ever need to play music in a key you have not practised on short notice.

In the case of the second option, you'd be learning the keys in an order following the circle of fifths. Learning them in this order means that each scale adds one additional accidental, minimising the difference in fingering pattern between each scale you learn.

C, F, G, D, B♭, E♭, A, A♭, E, D♭/C♯, B/C♭, G♭/F♯

This is roughly the order in which music curricula teach the keys and their corresponding key signatures. Someone following such a syllabus on an instrument like the flute or clarinet would learn the keys over many years, playing a substantial amount of music in each key over that time.

This will create a deep familiarity with all of the standard scales, but does require a lot of music organised by key signature. There is a good chance that much of it won't appeal to you. Even finding a large enough volume of music can be a notable burden in itself because ocarinas don't have the same institutional teaching traditions as mainstream orchestral instruments.

With regards to finding music to practice:

- I have a collection of links to ocarina friendly sheet music.

- Music collections for similar instruments may also be adaptable, although finding things that fit in range can be challenging.

Due to the range of single chambered ocarinas, music in sharper or flatter keys tends to be modal in nature, or in a major scale with the tonic in the middle of the range. Music for multichambers is less constrained in that way.

Of course, it is also possible to combine the two approaches. In this way, you would start by learning to play in the keys you need to play the music you want, and learn to play in the other keys afterwards.

Reading accidentals in the body of music

To get comfortable reading accidentals, I recommend going through all of the notes on your instrument from bottom to top chromatically and practising both sharpening and flattening each one. For example, you may play C—C♯, C—C♭, then C♯—C♮, C♯—D♮, and so on for the rest of the notes.

Once you can do this easily, find some music that uses a small number of accidentals, and practice reading it.

Audiating sheet music in different keys

Audiation is the ability to mentally hear music. It can be used to read sheet music 'in your mind's ear', much like you would read English without speaking. Being able to audiate music is helpful for knowing what it sounds like without needing to play it, as well as having an internal reference to check your intonation.

There is a good chance that you may have started to develop this skill for music in the C scale, but how would you start to do so for music in other keys? How can you learn to correctly audiate the accidentals in the respective scale, so that the melody sounds correct?

The process of learning to audiate music in different key signatures is much the same as learning to play those keys on an instrument:

- Choose one key signature to start with.

- Play music in that key signature on an instrument in a loop.

- As you do this, hear the music and imagine the same sound.

- Once you can hear the music internally, stop playing but continue hearing the melody in your mind.

- Read the whole melody in your head, without playing it on an instrument.

Once you're comfortable doing this for a few melodies, try reading some new sheet music in the same key using similar rhythmic and melodic figures. Audiate it in your head, then try playing it. Did they sound the same? You may find that playing or singing the scale, as well as the note transitions within the scale, will help you to audiate music more easily and accurately in the same way that it can help you internalise the fingerings on your instrument.

Learning how to transpose music in your head could also be helpful. Start by listening to something played in one key and audiating it. Then, listen to the same music again, transposed up by a semitone, and audiate it. Then, try to audiate the music in its original key, followed by the transposed key.

Closing notes

Learning to read sheet music with accidentals and key signatures is a matter of first building the muscle memory that you need to move between the notes in that scale, and secondly, associating those finger patterns with their representation in music notation. Depending on your goals, there are several ways to approach this, but the main thing is to build up your skills over time by practising a diverse range of music.