Getting rhythm

Rhythm is the foundation of music, and the basis of all rhythms is a beat, a steady, repetitive division of time. It's like the 'boom, boom, boom' you hear in electronic dance music, the regular tick of a clock, or the pattern of your feet hitting the ground as you walk at a steady pace.

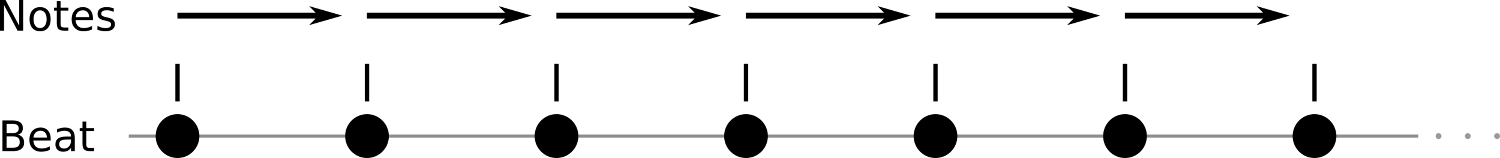

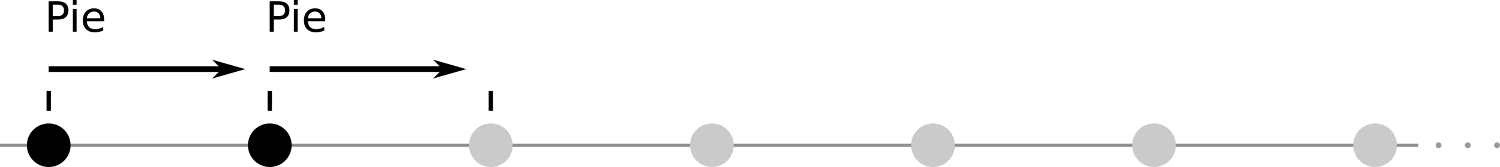

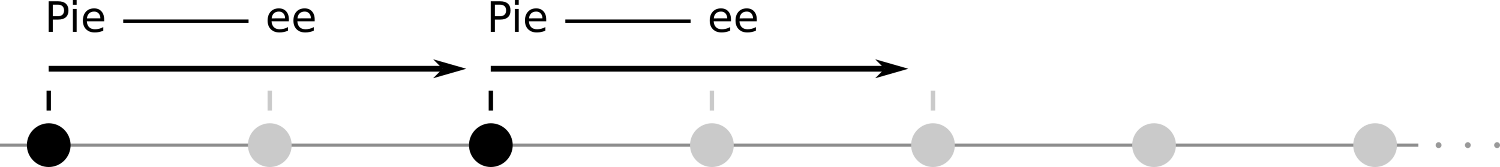

If you were to draw a beat as blobs on a timeline, it would look something like this; notice that these are not 'notes' yet, just pulses in time. You can also hear how this sounds using the tool below.

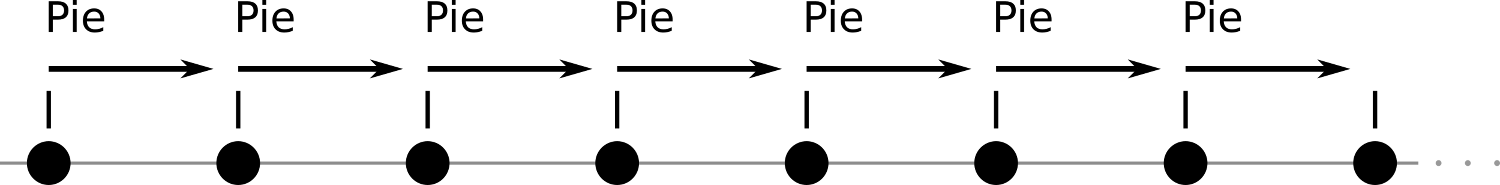

The beat can be thought of like a clothesline supporting your laundry, and we 'hang' notes from it. For example, a note can start at the beginning of one beat, and end just before the next beat.

In real music, there are often many layers of notes played to the same underlying beat, on multiple instruments, all happening at the same time. Think of an orchestra: the conductor is marking the beat, with every instrument playing its own unique melody line.

But let's keep things simple. To start with, give this a try:

- Find yourself a metronome. It's easy to find web-based ones if you search for 'metronome'.

- A metronome is a tool that produces a steady beat, measured in beats per minute (BPM). 60 BPM is 1 click per second.

- Listen to the beat, and clap when you hear a click.

The metronome is marking a regular beat, and the sound of your clap is a 'note' that you're playing over it. You may also find it useful to say a one syllable word with every clap, such as 'Pie'.

In real music, notes can fit around the beat in many ways. It can be subdivided, where each beat is split into two or more sub-beats. Alternately, notes can be held to span a duration longer than a single beat.

Subdividing the beat

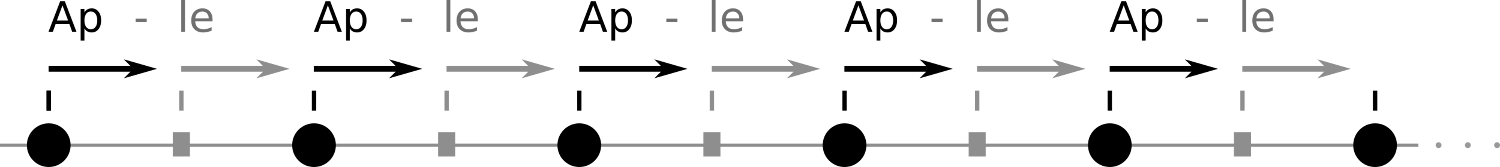

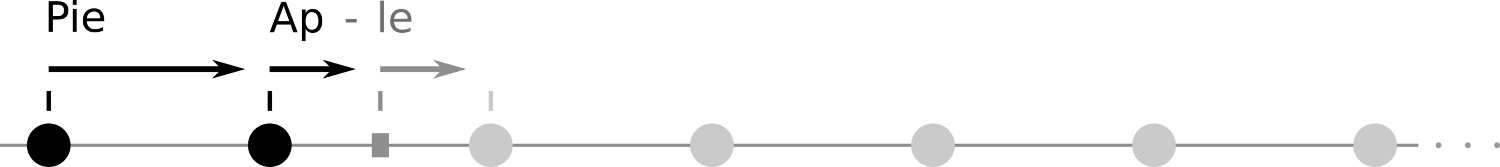

Let's start by getting a feeling for a rhythm that subdivides each beat into two. You can easily hear how that would sound using a metronome:

- Start by doubling the tempo of your metronome to 120 BPM.

- Clapping every other click is equivalent to what you were doing before, one note per click at 60 BPM.

- Clapping every click at the doubled tempo is thus equivalent to splitting each beat into two. You may find it helpful to clap alternate clicks louder.

Spend some time practising the subdivision into two using your metronome as a guide. You may find it helpful to associate this with a two syllable word, like 'Apple'. Once this subdivision starts to feel natural, return the metronome to 60 BPM and try clapping it without the audio guidance.

One note over multiple beats

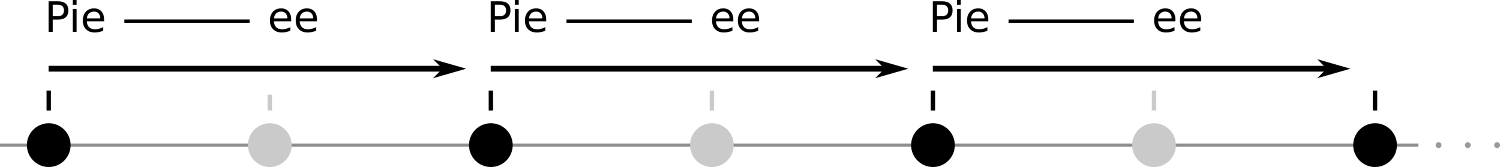

Notes can also span the duration of more than one beat. Using the clothesline analogy, if your 'one beat notes' were a t-shirt, the longer notes would be something wider, such as a towel.

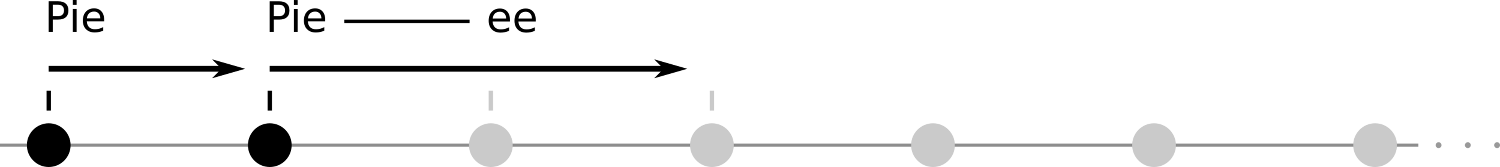

For example, to clap a note with a duration of two beats, start with your metronome at 60 BPM, and then clap every other beat that you hear.

You may find it helpful to count these: 1, 2, 1, 2 ... clapping on 1, and ignoring 2. We can do this with our word association by extending the last sound of the one-beat word, like 'Pie-ee'.

Note that you may hear the beat called the 'pulse'. The terms are used interchangeably, but aren't perfectly synonymous. The term 'beat' can refer to the overall beat, and also subdivisions of it. The term 'pulse' always names the undivided beat, what you'd tap your foot to.

Early, late or in-time?

How do you know if you're preforming these rhythms correctly? The metronome is guiding your claps, but do they perfectly align with it? You can start to develop a sense for the sound of a note that is early, late or in time using the following exercise:

- Place both of your hands palms down on a table.

- Lift your two hands, and place your left hand before your right. You'll hear and feel two sounds.

- Now gradually reduce the time between when your hands hit.

- Eventually, both hands hit at the same time, and the two sounds become one.

- And continue, such that your right hand hits the table first, and you'll once again hear two sounds.

The following tool also allows you to hear this. Initially, it plays two sounds perfectly in time. If you drag the 'phase' slider left or right, the second click will sound early or late.

You may want to try putting this into practice by clapping to a metronome. Doing so, you may notice that something strange happens when you're perfectly in time: the metronome click and your clapping start to merge into a single sound.

It does not matter whatsoever if you can do this perfectly straight away, as rhythmic accuracy is something that will develop naturally over time. We will be discussing this later.

Rhythm figures

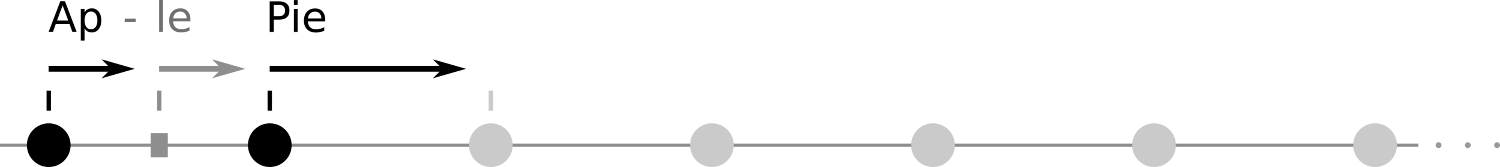

In a previous exercise, you learned how to clap different rhythmic subdivisions.

- One note per beat

- One beat split into two notes.

- A note that spans two beats

Simple patterns like these can be seen as analogous to 'words', being building blocks that can be assembled in any order. By developing a familiarity with how these figures sound when you play them in different combinations, you can develop an intuition for the 'possibility space' of rhythms that can be built using these figures.

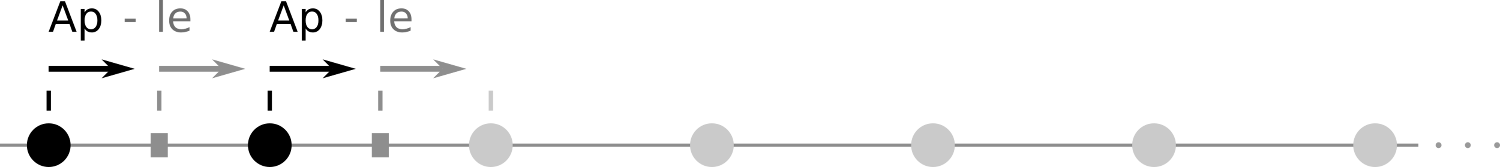

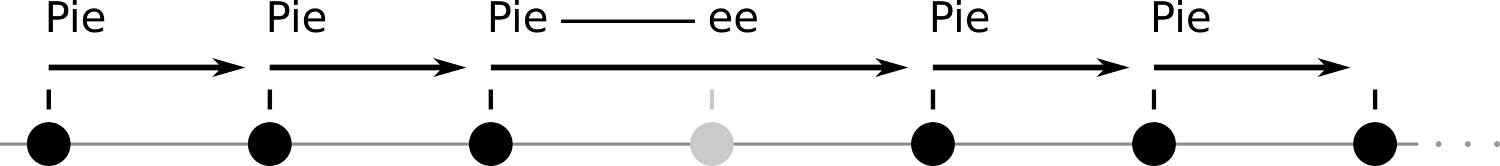

Choose one of the figures and follow it by each of the other figures, including repeating the same figure. This is what you get starting with the one beat note:

Take one of these figure pairs and practice clapping it to a metronome repeatedly until it starts to become muscle memory, so you don't have to think about it. Then do the same thing with the other two. It may take a few days to feel fully natural.

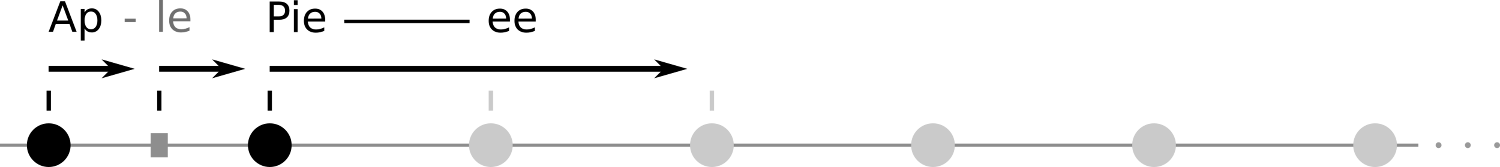

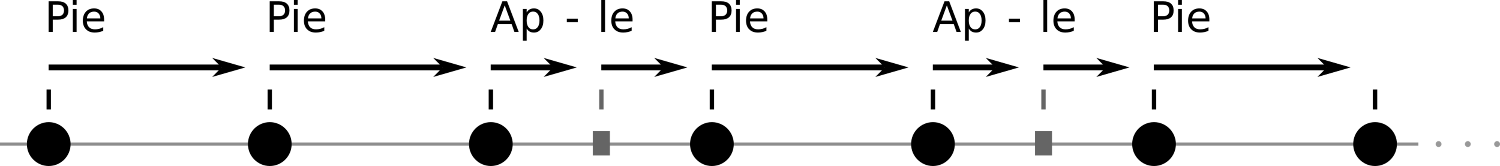

Next, you just repeat this process for the other two figures. Here are the patterns starting with one beat split into two:

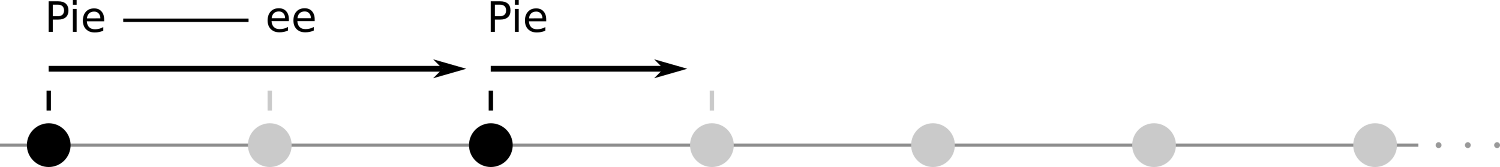

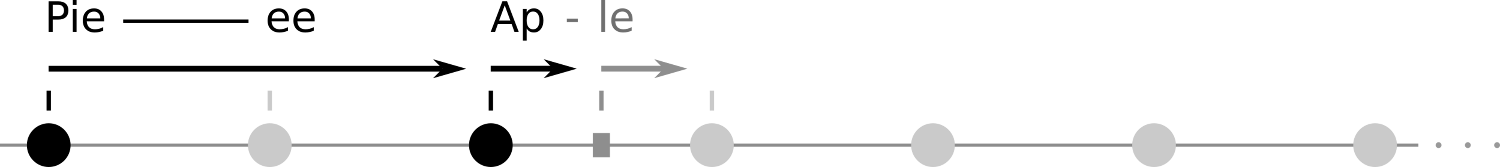

And here are the patterns you get when starting with a two beat note:

If you practice these every day for a few days, you'll start to internalise the sounds of these combinations. Regular practice is important because the mind will only retain information that you are using.

But with that practice, having learned all of the possible combinations of these patterns, you'll find that you can clap rhythms making use of the figures in arbitrary orders, flowing one figure into the next.

Beat grouping and time signatures

Humans like patterns, and music is not excluded from this. Have you heard someone counting 'one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four ...' in time with a song?

The beats of a rhythm are typically grouped into twos, threes, or fours. Try clapping groups of four beats to a metronome, and emphasise the first of each group by clapping louder. You may also find it helpful to count the beats, 'one two three four ...', in time with the metronome.

Also, repeat this exercise with groups of three beats, and groups of two beats, clapping the first louder. How does this feel?

Rhythmic groupings are called a 'time signature', which is expressed as two numbers written one above another, or alternately two numbers with a slash. Here are some common ones:

- Rhythms based around groups of two beats are called 2/4, read 'two four'.

- Rhythms based around groups of three beats are called 3/4, read 'three four'.

- Rhythms based around groups of four beats are called 4/4, read 'four four'.

These terms may seem pretty arbitrary. Why, for instance, do we say 2/4, instead of just saying 'rhythm in 2'? The terms originate from how rhythms are notated in sheet music, and yes, to some extent are overly complex. For the time being it is fine to treat them as arbitrary names, '2/4' meaning 'a rhythm based on groups of two beats', etc.

There are other groupings besides just two, three and four, but they are rare in mainstream music.

The grouping of time signatures shows up everywhere in the structure of music, from the emphasis of beats, as well as repetitions of melodic and rhythmic patterns. How it does so is diverse and varies a great deal between genres.

For one, it can often be easily heard in the percussion of a song, like the following drum pattern I'm sure you'll have heard before:

'Boom', 'tiss', 'Boom', 'tiss'...

I'd recommend listening to a range of music that you enjoy and count along with it, seeing if a grouping of two, three, or four aligns best. Probably, most of them will be grouped in fours, but some will be in threes. The song 'Delilah' by Tom Jones is an example of a song in threes. Next, search for '[song name] time signature', and see if your guess was correct.

The beats that are emphasised are called 'strong' beats, while ones that are de-emphasised are called 'weak beats. Here are some possible emphasis patterns that you'll hear within music in a 3/4 time signature. The first one is emblematic of the 'waltz' dance.

Strong, Weak, Weak ...

Strong, Strong, Weak ...

Strong, Weak, Strong ...

There are many fantastic resources about rhythm patterns, and to learn more, I'd recommend searching for things like 'rhythmic patterns within [time signature]', and 'common rhythmic patterns within [genre of music]'.

Performing rhythms on the ocarina

With some familiarity with basic rhythm patterns, it is easy to start applying them to the ocarina.

Internalising the beat

Internalising the beat, hearing a beat within your head, enables you to play in time without a metronome.

- Put on a metronome at a tempo you are comfortable with.

- Try to imagine the sound of the metronome in your head, and possibly tap your foot along with it.

- Once you're comfortable, turn off the metronome and continue to imagine it, and/or tap your foot at a regular beat.

Once you feel you've got the hang of this, try clapping a regular beat to your internal metronome and record it. How does it sound to you?

It can take a few days to be able to do this without thinking about it, and, as noted previously, rhythmic accuracy is a skill that will naturally improve over time.

Tonguing to a rhythm

Hold your ocarina normally, and:

- Finger a single note, for example 'G' in the middle of the range.

- Try playing a note every beat, starting the first note and separating following ones using your tongue.

- Then try tonguing some of the other rhythmic figures we've been practising.

Here are a few rhythms. First clap them, and then play them on the ocarina.

And once you've got the hang of these, make up your own rhythms built from the three figures you've learned.

Before playing rhythms on the ocarina, I'd advise practising clapping the figures and the combinations (one figure after another) until you can perform them without using vocalisations. Vocalisations can be a useful tool, to help you get started and work as a memory aid. However, they can get in the way, as it's impossible to speak while blowing a wind instrument.

Also, creating emphasis (strong and weak beats) on the ocarina requires a bit of ingenuity, as the instrument cannot easily change its volume. If you just blow harder, the note will sound sharp. We mostly emphasise notes by varying our articulation and ornamentation, and will be exploring this in Introducing musicality.

Learning more rhythms

What's been introduced so far may seem very simplistic, but in actuality, you now have the tools to learn any rhythm you want.

Firstly, once you've practised the rhythm figures in this article to a point that they have become 'muscle memory', and they can be performed effortlessly, it is easy to learn how they are notated in sheet music, and start sight-reading basic rhythm notation. See The essence of rhythm notation.

And then it's just a matter of building your vocabulary of figures and learning how they sound when played before and after other figures. There are numerous ways of finding more figures to learn:

- It is easy to start building your own repertoire of rhythm figures from the music that you are learning by observing the patterns that it uses. This can be done using sheet music, or cutting up and looping small parts of song recordings in an audio editor.

- There are numerous books, websites, and apps of rhythm exercises.

- Graded music curriculums, which introduce rhythms of increasing complexity gradually, can also be useful.

With these approaches, try to break the rhythm down into short figures that align with the beat, and relate to other figures in a way that form coherent 'units'. For example, a figure that ends in the middle of a beat may be harder to combine with other figures.

Learning figures in the context of other figures allows you to develop a full intuition for the possibility space of rhythms. By comparison, if you internalise the rhythm of an entire song from start to finish, you'll be able to play that song, but won't be able to apply the knowledge to other music so easily.

There are numerous systems for adding vocalisations to rhythms, including the word associations demonstrated above, 'counting', and 'Kodály rhythm syllables', which are discussed in the article Reading rhythms in sheet music, and thousands of other resources available online. They can act as a memory aid, but the goal should always be to practice the rhythms to a point that such aids fall away.

Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) was a Hungarian composer and music teacher who promoted music education in schools and developed a method for the straightforward teaching of musical concepts.

The 'counting' approach can also be used to work out the sound of rhythms in sheet music without needing to first hear them. As of writing, this is one of the most common approaches to teaching rhythm. However, this process involves using logical analysis to 'reverse engineer' the sound of a rhythm. My observation is that it tends to cause beginners to stall frequently while playing, and it can be frustrating.

I'd recommend starting by listening to and clapping the rhythm figures you are learning, and associate that to notation after you can already perform it reliably. My feeling is that learning rhythms without first hearing them is rather like trying to learn to pronounce a foreign language you have never heard.

Given our ubiquitous access to technology, there are numerous ways of hearing rhythms:

- Take an audio recording of a song and cut it up using an audio editor. How to do so is discussed in Playing your favourite songs on the ocarina.

- Use a notation software like MuseScore, allowing you to enter notes and play them back.

- Work with a teacher who can perform rhythm figures for you to copy by ear.

- Use the exercises on the page exercises for reading rhythm.

Learning from recordings of human performances will help you to internalise the nuances of human performances, as varying the exact timing of a rhythm is one of many expressive tools used by musicians. Rhythms are commonly not performed exactly as written.

Lastly, as you learn more rhythm figures, the number of possible combinations increases rapidly, and thus it becomes more difficult to know how to practice them effectively. What I'd recommend is to look at an assortment of real music and see which rhythm figures often follow other figures, as many possibilities rarely if ever get used.

Developing rhythmic accuracy

As was noted above, rhythmic accuracy is something that will develop naturally over time as you practice, and against common belief, it does not matter if you are good at it straight away. Making rhythmic errors when you first start out definitely does not imply that you're 'not musical'.

Developing rhythmic accuracy is a process of listening to the timing of your note and gradually making corrections. With experience, your ability to hear errors also will improve. It might help you hear what's happening if you close your eyes or blindfold yourself, as people naturally prioritise what they see over what they hear. In this case, you want the opposite, and eliminating visual stimulus can help.

You may find the following tool helpful. It visualises the timing of your clicks, in relation to a metronome. When you are exactly in time, the vertical bars will align.

Note that if the bars do not align even when you click in time, you need to adjust the 'latency compensation' slider. Computers have a delay between when a sound is triggered and when you hear it. Unfortunately, it is impossible to compensate for this automatically.

Closing

You now have a solid foundation in rhythm that will help you learn rhythms from simple to very complex. All rhythms are based on these same concepts, and more complex ones just use smaller subdivisions, or group beats in other ways. Just keep growing your experience over time.