Kinaesthetic rhythm exercises - quarter notes, quarter rests, and eighth notes

Sheet music represents two different things at once, the rhythm of the music, telling you when notes are played, and the pitch to play on your instrument. Let's start by learning how to read some basic rhythms. First we'll learn to clap them by ear, then connect this with notation.

The foundation of all rhythms is a 'beat' or 'pulse'—a regular division of time. You can hear a beat using the tool below.

As you listen, notice how the click resembles the steady hits of your feet while walking at a steady pace (try it if you like), or the tick of a clock. If we were to draw it on a timeline, it would look something like this:

The first step in learning to read rhythms is to start internalising the pulse, learning to hear a steady pulse in your head:

- As you listen to the metronome imagine the same sound in your mind, or feel it in your body.

- You may also find it helpful to tap your foot, clap, or walk in time with the pulse.

With a few days of practice you'll start to be able to hear a regular beat in your head. If you'd like more information about the logic of rhythms, see the article Getting rhythm.

Kinaesthetic rhythm reading

Kinaesthetic rhythm reading or 'audiation', is the ability to hear a rhythm in your head immediately upon seeing some notation. It is easier to develop than you may expect.

People are really good at both imitating things they are hearing, and recognising visual patterns. Thus if you listen to and clap a rhythm while looking at the notation, you can train yourself to instinctually know what notation sounds like.

You may try this with the following sample, click 'play', listen to the sound that you hear, and clap when you hear the piano note, and repeat this a few times.

If you were to do this for a few minutes every day for a few days, you'll find that you start to hear the rhythm upon seeing the notation, much like your subconscious pronounces English words to you when you read.

Note that if you are familiar with 'counting', and how to use that to consciously analyse the sound of a rhythm, try to suppress the urge to do so, the goal is to hear the rhythm in your mind as a sound, like it was played on an instrument.

Persistence and regularity is super important for this process to work because the human mind is lazy, and only remembers things that you're actually using regularly.

Skipping a beat

A rhythm formed by playing a note on every single beat sounds really monotonous, right? In real music we vary rhythms in a few ways, and one is to ignore some beats. We call these 'rests', and one kind of rest looks like this:

Listen to each of the following 4 examples of rests, and clap each one 10 to 20 times while looking at the notation every day for a few days, and these too will start to be internalised.

Subdividing the beat

Other ways that rhythms are formed include splitting each beat into multiple sub-beats, and playing a single note over the duration of multiple beats.

First, lets learn what a basic subdivision sounds like.

In real music you'll more often see that drawn as follows. The two flags are joined together into a 'beam' as it improves readability.

In notation different shapes of note symbol represent different durations of time, and you can see some of the common ones below.

It can be intuitive to think that the 'whole note' represents a whole beat, but it doesn't. These note symbols actually have no innate duration.

Rather, we can choose any symbol to represent a single beat, and the others are defined in relation.

- A half note is half the duration of a whole note

- A quarter note is half the duration of a half note

- Etc...

Commonly the quarter note is used to represent one beat, and thus the half note would represent two beats, and the eighth note represents half a beat. This could seam overcomplicated, but is actually quite elegant once you start to develop an intuition for how different subdivisions sound.

Which note symbol represents a whole beat is communicated by something called a 'time signature', and we'll get to that a bit later. It is also discussed in detail in the article The essence of rhythm notation.

Reading rhythms using all of these different note symbols can be learned by ear in much the same way, but for now lets look at rhythm figures.

Figures, the building blocks of rhythms

A good way to develop an intuition for many different kinds of rhythm is to practice simple examples of a rhythm pattern in different arrangements.

For example, the 'long short short' pattern introduced earlier can be practised in two different orders, with the long note at the start:

Or flipped, with the long note at the end:

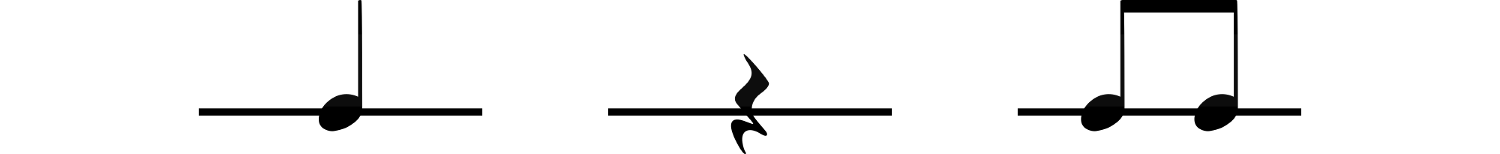

Figures are essentially like words, or 'lego bricks'. They can be assembled in any order to form arbitrary rhythms. These are the figures that we've been using so far—the quarter note, pair of eighth notes and the quarter rest:

And this is useful because once you start to internalise the sounds on common figures, it starts to be possible to read any kind of rhythm. If you try reading the following rhythms there's a good chance you can do so easily, even though you've never seen the notes in this exact order.

Practising the combinations

When you're practising figures, it can be helpful to list out every possible way that they can connect. You choose one of the figures, and then follow it with every other figure:

- Quarter followed by quarter

- Quarter followed by a pair of eighth notes

- Quarter followed by quarter rest.

Then make the other combinations, substituting the first figure for a pair of eighth, notes, then quarter rest.

For the 3 figures we have been using so far, there are 9 possible combinations. Listen to each of these one by one, and clap it 10 to 20 times every day for a few days.

Grouping and time signatures

Have you ever heard anyone counting '1,2,3,4, 1,2,3,4 ...', or perhaps '1,2,3, 1,2,3 ...', in time with a song? Perhaps you've also done so yourself. What they are counting is the grouping of beats in the music.

The beats in music are commonly arranged into regular groups of 4, groups of 3, or in other ways.

In notation, these groupings indicated by a 'time signature', two numbers stacked vertically at the beginning of the staff. You'll also see them written as two numbers with a slash in text, like '4/4'.

- The bottom number in this pair names a type of note symbol.

- The the top number tells you how many of them are in each group.

Because we commonly use the quarter note to represent one beat, a grouping into 4 is commonly notated with the time signature 4/4, read 'four four', and which literally means '4 quarter notes'.

You can hear this below, and in the following examples the last beat of each group has been marked with a pair of 8th notes to make it easy to hear. Notice also that the groups in notation are separated by vertical 'bar lines'.

Likewise, a grouping into 3 beats is called '3/4':

And a grouping into 2 is called '2/4':

If you listen to a variety of music that you like try to notice how the beats are being grouped, which would tell you the time signature. This is also discussed in more detail in The essence of rhythm notation.

Random rhythms to practice

This tool generates random rhythms using the figures you learned above.

First try to read the rhythm without listening to the audio, and if you struggle listen and clap a few times. Within a few days or weeks, you'll be reading everything this generates without trouble.