The essence of rhythm notation

As we discussed in Playing the ocarina with sheet music, rhythms are notated using symbols called 'notes':

- A half note has half the duration of a whole note.

- A quarter note has half the duration of a half note.

- And so on.

But a half, quarter, eighth of what? In fact, these symbols alone have no absolute value. We only know the time duration of any note after we assign one of the symbols to represent the duration of a single beat.

For example, we commonly use the quarter note to represent one beat:

The durations of the other notes are then defined in relation. In this case, the half note would represent two beats, the eighth note would represent half a beat, and so on.

This assignment is communicated to you by something called a 'time signature', and sheet music can and does vary in how it assigns the note symbols to the beat. It may seem needlessly complex, but there are good reasons for this that will be addressed later.

Throughout this article, I will use the American names for note durations, as they have a direct connection to common language and are, in my opinion, easier to understand. In the UK, the note durations have different names:

- Whole note – semibreve.

- Half note – minim.

- Quarter note – crotchet.

- Eighth note – quaver.

- Sixteenth note – semiquaver.

- Thirty-second note – demisemiquaver.

Time signatures

Rhythms are frequently organised into fixed numbers of beats, as repeating patterns are one of the features that make music sound musical. For example, it is common to find rhythms grouping beats into fours. If you have ever heard someone counting 'one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four, etc.', in time with the beat of a song, they are counting this grouping.

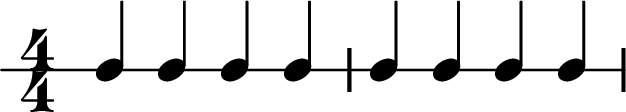

This is how it sounds:

The other common beat grouping you'll hear is three. If you consider a rhythm like this while walking and count 'one, two, three, one, two, three, etc.,' you'll notice that each group's first 'hit' occurs on a different foot, giving it a swaying feel. The waltz dance uses this grouping, as does the mazurka.

Sheet music communicates these groupings using the time signature: two numbers placed one above the other at the start of the staff. In text, you'll also see them written as two numbers with a slash.

The time signature '4/4' (read 'four four') looks like this:

A time signature is not a mathematical fraction, even though it resembles one visually. Rather, it tells you how many of a given note symbol you will find in each group:

- The bottom number names one of the previously mentioned note types, '4' being a quarter note, '2' being a half note, and so on.

- The top number tells you how many of those notes will be in each group.

Thus, the time signature '4/4' can be read as 'four quarter notes'.

When we write music, we usually use vertical bar lines to separate these groups, which look like this:

The space between any two bar lines is called a 'bar', and we can write two bars of quarter notes like this:

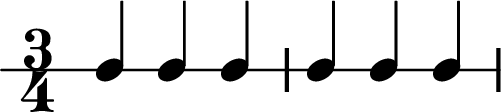

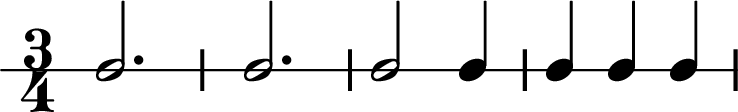

Rhythms based on a three-beat grouping are commonly written using the time signature '3/4', and look like this:

Given the available note types, we tend to use the quarter note as the base reference, as it allows a good range of freedom to create longer and shorter notes. If you organise the notes in a graph, with each level going downwards halving their duration, the quarter note lands in the middle.

How time signatures relate to the beat.

It is commonly taught that 'the top number in the time signature tells you the number of beats in the bar, the bottom number says which note is assigned to the beat'.

This statement can cause considerable confusion because it works in a few cases, but it is not universally correct. Using this explanation, one would be led to assume that the time signatures of '3/4' and '3/8' are equivalent, with the second using a shorter note value. However, this isn't true.

In actuality, the time signature '3/8' most often means 'one beat split equally into three', due to a convention known as 'compound time' that will be discussed later. The time signatures '3/4' and '3/8' sound very different when played.

The relationship between time signatures and the beat is actually a matter of convention. Musicians learn from experience that '3/8' means 'one beat split equally into three'. However, that information is not included within the time signature itself.

Here are a few more common time signatures and their typical interpretations. It doesn't matter if you understand these right now, as they will be explained later in the article.

- 4/4: four beats, the quarter note assigned to the beat.

- 3/4: three beats, the quarter note assigned to the beat.

- 2/2: two beats, the half note assigned to the beat.

- 3/8: one beat split equally into three.

- 5/4: five beats, the quarter note assigned to the beat, often constituting one group of three quarter notes and one group of two quarter notes.

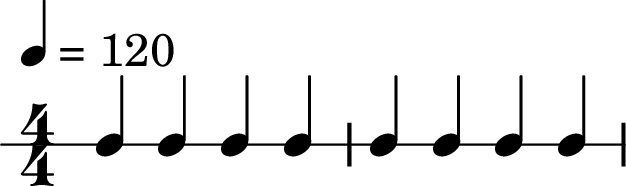

Sheet music can also indicate the beat in other ways; one method is to use a metronome mark, which assigns a type of note to a specific number of beats per minute, as shown in the example below.

In music written using eighth notes, it is also common that the beaming of the notes will indicate the intended beat structure. Beaming is when the flags of sequential notes are joined together.

Bars and note durations

Each bar may contain notes totalling the duration specified in the time signature, and it is conventional to ensure that bars are always 'full'.

In 4/4, we can have a bar of four quarter notes. Alternately, we could have two half notes, as a half note has the same duration as two quarter notes. Likewise, a bar may contain one whole note or eight eighth notes.

However, you'd be more likely to see that written as shown below. The flags of shorter notes are often beamed together to improve readability.

We can combine notes of any duration within a bar, as long as the total duration of the entire bar equals the note value specified in the time signature.

The same applies to other time signatures. Thus, in 3/4, we can have a bar of three quarter notes, a quarter note and a half note, or any other combination of equivalent duration:

Some explanations of rhythm notation state that 'a whole note is a whole bar'. This statement is true for time signatures like 4/4 and 2/2, but it is not generally correct. Rather, the note value equivalent to a whole bar changes depending on the time signature.

In 2/4, that is a half note; in 3/4, it is the dotted half note, which you can see below (the meaning of dotted notes will be introduced shortly). That a whole note is equivalent to the duration of a whole bar in 4/4 and 2/2 is a coincidence.

Hearing and experimenting with rhythm notation for yourself

Now that you know the logic behind basic rhythm notation, it's a good time to get some practical experience with how this notation sounds. You may assume that doing so requires learning to read rhythms, but that's not the case.

You can use a music notation program like MuseScore, enter rhythm notation, and the software will play it back to you. This will give you practical experience with how things sound, which will help immensely when you learn to read rhythms.

MuseScore can be used to recreate the rhythms demonstrated in this article so far. As you get an intuition for it, you can start forming rhythms of your own from scratch, or copying the notation from any sheet music you have, or copying well-known rhythms.

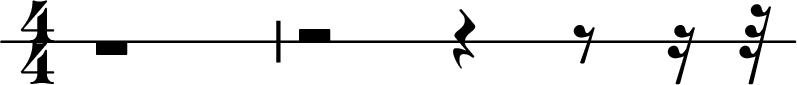

In doing so, you may notice that rhythms can be formed from arbitrary collections of note durations, as long as they align with the beat. If you just assemble notes with random durations, the sense of grouping vanishes and the rhythm will sound weird:

Dotted notes and ties

So far, all of the rhythms we have explored have been based on simple ratios, such as halves and quarters. However, music also uses rhythms based on other note durations, such as three beats or one and a half beats.

Music notation can show these rhythms using dotted notes and/or ties.

Dotted notes

A dot placed after a note indicates that its duration should be extended by half the written value. This has been shown in the context of two half notes. If you were to dot the first one, its duration would be extended by a quarter note. The following note must be shortened to a quarter note so that the two notes together have the same duration.

Thus, a dotted quarter note lasts one and a half beats. A dotted eighth note has a duration equal to three sixteenth notes. These are shown below in the context of a pair of notes without dots.

Notes can also be followed by two or more dots, with each additional dot increasing the note's duration by half of the value added by the previous dot. A double dotted quarter note has a duration of a quarter note plus an eighth note, plus a sixteenth note.

Dotted notes are used in various ways in rhythms, and it would be worthwhile to examine a range of different music to see for yourself.

Ties

A tie is a curved line drawn between the heads of two notes, joining their rhythmic value into a single note with their cumulative value. For example, a pair of tied half notes has the same duration as a whole note.

Ties are used for several reasons. First, multiple tied notes can be used to create notes with a longer duration than a single bar. A pair of tied whole notes in 4/4 would span two bars and eight beats. To span an even longer duration, three or more notes can be tied together.

Ties are also used to notate any kind of rhythm where the duration of a note is played across a bar line:

We write long notes and bar-crossing rhythms like this instead of using single note symbols with a duration longer than a bar. We do this due to the convention that bars should always be 'full', containing a collection of notes adding up to the same duration in every bar. This results in a consistent visual reference for the length of each bar.

Double and quadruple whole notes exist, but they are used mainly in time signatures like 4/1, primarily in a historical context. Initially, what we now call a 'whole note' was the 'one beat note'. Eventually, there was a shift towards notating music using shorter note values by proportionally scaling down all of the notes, and the longer note symbols fell out of use.

However, returning to ties, they are also used for notating rhythms within a bar, where they would improve readability. The two rhythms written below are equivalent in how they would be played, but you would probably see the first one rather than the second in real music. Splitting the rhythm into multiple tied notes more clearly shows where the constituent beats are.

Ties also appear in music with many shorter-duration notes, where the rhythm crosses the middle of the bar. This is also done to improve readability by using note symbols to show where the underlying beat of the music is. Both examples below show the same rhythm, but the first is more common.

Lastly, for this discussion of ties, they are used to write rhythms with notes of unusual durations. A one-and-a-quarter, three-quarter rhythm can be written using ties and dotted notes like this, for instance:

Rests – not playing anything

Another way to add interest to a rhythm is to insert gaps or not play notes. In music notation, such a 'gap' is called a 'rest'. Rests are essentially note symbols that mean 'do nothing', and ones with equivalent durations for all note types exist.

When music is written, rests may be substituted for any note of equivalent duration, depending on how the composer wishes the rhythm to sound. They take up the time of the equivalent note but are not played in any way. They may be dotted, but tying them does not make sense.

The example below illustrates how rests look when written on a staff. The whole rest and half rest are always written on the middle line of the staff, and an easy way of remembering the 'whole' rest vs. the 'half' is that the whole rest looks like a 'hole' in the line.

The other symbols are often also written on the middle line, but they may be shifted up or down to align with the surrounding notes if it improves readability.

Note that while a whole note is only equivalent to a whole bar in 4/4 (and equivalents like 2/2), the whole rest is used as a whole bar rest in most time signatures.

Tuplets

A limitation of the note symbols used by rhythm notation is that they always split time uniformly by two, for, eight and so on. Tuplets are a way of notating rhythms that use a different subdivision like three, five, or seven.

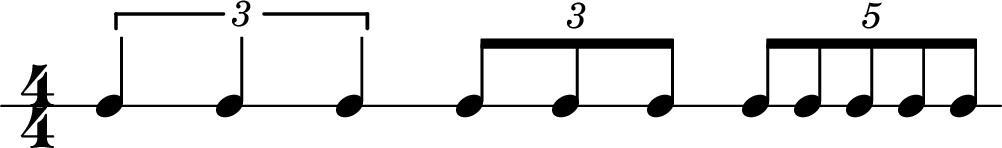

Tuplets can be recognised by a number written above a group of notes indicated either with a bracket, or beaming in the case of note durations that can be beamed.

A very common kind of tuplet is a triplet. Triplets can be recognised by number '3' written above a group of three notes with equal duration. To perform one, the notes are played in the time of two notes by splitting the total time the two notes would take equally into 3.

For example, three 8th notes played in the time duration of two 8th notes, which sounds like this:

A triplet also has the same meaning at different timescales, for example a quarter note triplet means 'play 3 quarter notes in the time that would be taken by 2 quarter notes':

There are different kinds of tuplets, and they have different common interpretations outlined below:

- Duplet – two notes in the time of three.

- Triplet - three notes in the time of two.

- Quadruplet - 4 notes in the time of three.

- Quintuplet – five notes in the time of four.

- Sextuplet – six notes in the time of two.

- Septuplet – seven notes in the time of four.

- Octuplet – eight notes in the time of three.

- Nonuplet – nine notes in the time of two.

Tuplets may also write a ratio above a note like '5:2', which would indicate fitting five notes into the space of two.

Compound time

In 3/4 time, you have a group of three beats, but what about dividing a single beat into three? Technically, it isn't difficult for a musician to do this, and it sounds like this:

But how could this be notated? A clean way would be to use three eighth notes, the duration of a dotted quarter note, for each beat. Unfortunately, the lower number of a time signature conventionally refers only to whole note values, so you can say 'one quarter note per bar' or 'one eighth note per bar', but there's no way to say 'one dotted quarter note per bar'.

One option is to use the time signature '1/4' and notate every bar as a triplet. It works, but doing that for an entire piece of music would be visually cluttered.

Instead, the convention is to take the dotted quarter note that cannot be represented in the time signature and break it into three eighth notes. Thus, the time signature of '3/8' actually represents one beat with a duration of a dotted quarter note.

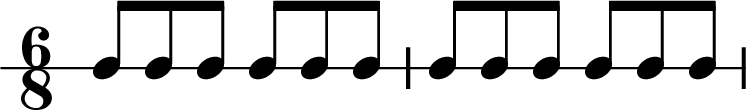

If a rhythm includes two or more dotted quarter note beats per measure, the convention is to take the base of '3' and multiply it by the number of beats. So if there are two beats per measure, the time signature is '6/8', for three beats it is '9/8', and so on.

- One beat: 3/8 – used in the French three-time Bourree.

- Two beats: 6/8 – the quintessential 'jig' found in traditional Irish, Scottish, and English tunes.

- Three beats: 9/8 – the Irish slip jig.

- Four beats: 12/8 – the Irish slide.

As noted earlier in the article, compound time is where the idea that 'the top number tells you the number of beats in the bar' no longer applies. Some sources have tried to address that by stating that there is a difference between the concept of the 'pulse', where you'd clap in a rhythm, and the 'beat', which is an arbitrary concept defined by the time signature in notation.

However, this explanation doesn't address the fundamental problem that the actual beat of the music, as felt by a listener, is not defined anywhere in the time signature. Thus, I think that discarding the idea that the time signature directly tells you the beat makes more sense.

The concept of 'beat' in music can be quite fluid. You may see instances of music notated in 6/8 where the beaming and structure mostly has two beats per bar, then switches to three beats, before switching back. This is called 'hemiola', a momentary change of beat for rhythmic ornament.

Irregular time signatures (5/4, 7/4, 7/8)

You will at some point run across irregular time signatures such as 5/4 and 7/4, and while they may seem scary they really aren't. What they commonly represent is a rhythm based on a mixed grouping of twos and threes.

For example, 5/4 typically represents a group of 3 and a group of 2. (1,2,1,2,3) or (1,2,3,1,2). Music in this time signature includes five time waltzes, and the jazz piece 'Take 5'.

Likewise, 7/8 represents music based on a triplet and two pars of 8th notes, and is felt with an irregular long, short, short pulse. These time signatures have quite a distinctive sound as we tend to perceive groupings like this as having a 'skip', a missing beat.

Closing notes

Rhythm notation uses note symbols that represent simple ratios among themselves. One of these symbols is defined to represent one beat, and the other symbols acquire their duration from it. Using this concept and some simple additions, such as dotted notes, ties, and tuplets, we can notate many different kinds of rhythm.

This notation is not complex. However, it is surprisingly difficult to explain clearly due to the note durations being defined in relation to themselves rather than the bar, and conventions like compound time. Many other sources have attempted to simplify these concepts, resulting in confusing logical inconsistencies that I have addressed throughout the article.

I'd recommend studying the rhythms in the music you enjoy. Utilise tools like MuseScore or other music notation software to transcribe rhythms, play them back, experiment, and hear how they sound for yourself. Notation is much more intuitive when you can also hear it.

There are several ways of learning to read and perform rhythms on an instrument, which are discussed in the next article in this series, Reading rhythms in sheet music.