Reading sheet music on the ocarina

Learning to read sheet music on the ocarina is not as difficult as you may think. Let's consider a simple question: Do you know how to drive, or can you swim? If so, think back to how you learned to do those things.

Most probably, you learned them gradually over a long period of time. Reading sheet music is likewise a learned skill that takes time to master. Yet you can learn the basics in just a few minutes.

The basics of sheet music

Sheet music can seem complex on first impression, mostly because it communicates several things at once:

- Which note (fingering) to play on your instrument.

- How long each note should be played for.

- Frequently, it also tells you how to play something stylistically.

Like written English, sheet music is written in lines, each of which is itself represented by a group of five horizontal lines, as shown below. Collectively, these lines are called the 'staff' or 'stave'.

Both the pitches and rhythm of a melody are shown on the staff using symbols called 'notes'. Several kinds of these symbols exist, all having common features that we'll get to in a moment.

The eighth and sixteenth notes are probably familiar to you, as these symbols are often used in culture to represent the concept of music. However, the whole note may not look right, or may seem to have something missing.

Notes actually consist of multiple parts, called the 'stem', 'head', and 'flags', which communicate different things:

The head marks a vertical position on the staff (much like a point on a line graph), telling you what note to play on your instrument. The head can be placed either on a line or in the space between two lines. Each position corresponds to a different fingering on your ocarina, and a few are shown below.

The appearance of the entire symbol (head, stem, and flags together) describes how long the note will be played for:

- A whole note consists only of a head.

- Adding a stem halves the duration of the note.

- Then, filling in the note head halves it again, and so on, as shown in the previous diagram.

Notes are read left to right. The following example depicts a series of successively shorter notes of the same pitch, with each next note to the right being half the length of the previous one. See the article The essence of rhythm notation for more information.

When you see music with successive note heads in the same vertical position, it means that the music is using a series of notes at the same pitch:

Note that the direction of the note stems, or the side of the note head they are attached to, carries no meaning. They are oriented depending on where a note is on the staff:

- When a note is placed below the middle line on the staff, the stem should be placed on the right-hand side and go up.

- When a note is placed above the middle line, the stem should be placed on the left-hand side and go down.

- A note placed on the middle line can have the stem going in either direction, depending on what is most readable in context.

Music is written like this because it makes the notation more compact.

The ABRSM music theory workbooks include many examples of 'nitpicky' things like this, and I'd recommend them if you want to learn more about the standard ways of writing music.

Learning to read sheet music on the ocarina

Because sheet music represents several things at once, we need to be tactful in how we approach learning to read it. I think the best approach to learn to read sheet music on the ocarina is:

- Learn to read some simple rhythms.

- Learn to read a small range of pitches and how to finger them.

Then, this process is repeated, gradually introducing more complex notation.

As with everything, we need to learn to walk before we run. That being said, reading complex music as a beginner is possible, and we touch on how to do so at the end of the article.

Learning to read rhythms

The foundation of all rhythms is the beat, a consistent division of time like the tick of a clock, a metronome, or the sound of your feet as you walk.

When some music is written, one of these note symbols is chosen to equal one beat, and the other symbols 'acquire' their duration in relation to it. In many cases, the quarter note represents one beat, like this:

- The bottom line shows a steady beat,

- and the top line illustrates how sheet music would show this: a series of quarter notes.

The note symbol that represents one beat can vary, and is communicated by the time signature: the two numbers at the start of the staff. In this case '4/4', which is pronounced 'four four'.

How time signatures work can be a bit arbitrary, and for now, it's enough to know that '4/4' tells you that the quarter note represents one beat. Thus, a half note is two beats, and an eighth note is half a beat. We will explore this fully in the article The essence of rhythm notation.

Reading your first rhythms

So, let's read some rhythms. The first thing you'll need is a metronome, which can easily be found as a web app by searching for 'metronome' online.

Set the metronome to a slow tempo, like 60 BPM. To start with, just listen to the click. You may also want to tap your foot.

We can start by clapping some rhythms. As we discussed, the quarter note represents one beat in a 4/4 time signature. Thus, to read this one, you just clap once per click, for a total of eight clicks. Continue doing this until you feel at ease with it.

The half note, which you can see below, represents a duration of two beats, twice as long as the quarter note. To read this rhythm, you listen to the metronome and clap once for every two clicks. It may help you to count the beats as you hear them: '1, 2, 1, 2, ...', clapping on 1, and ignoring 2.

The eighth note has half the duration of a quarter note, splitting each beat into two. To get a feel for playing them:

- Set your metronome to twice the tempo, so that it is marking both the beat, and the mid point between two beats.

- Practice clapping every time you hear a click, and continue until it feels natural. You may also find it helpful to say 'ap-le' or 'ti-ka' with each pair.

- Set your metronome back to 60, but clap as you were, splitting the beat in two.

Notice that when you have multiple eighth notes in sequence, the flags are normally joined together into a beam:

Finally, we can tackle a rhythm that mixes the different note durations. Once you get the hang of this one, find some blank manuscript paper (printable templates can be found online) and try writing out some rhythms using these notes.

Learning to read pitches

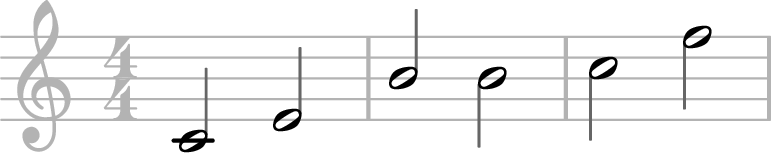

The heads of the notes draw patterns on the staff. For example, you may see a group of notes like this, ascending like a staircase:

These patterns correlate to equivalent patterns of finger movement on our instruments. If you play the following finger patterns, one note per metronome click, you have played the same sequence written in the notation above.

A short sequence of notes is called a melodic figure. If you practice the fingering of a figure like the scale run above for several days, it becomes muscle memory and will be effortless to perform.

At that point, it is trivial to associate the existing muscle memory with the corresponding notation, enabling you to recognise the sequence and perform the associated muscle memory 'as a unit', without needing to process the individual notes consciously.

Then, as you do this with hundreds more figures, you start to internalise the possibility space of what sheet music can represent. Music can be read by recognising and performing sequences of figures, much like one may build many different things from the same Lego bricks.

With practice, this process becomes a kinaesthetic response, a subconscious connection between some notation and how it will be performed. Once you have a large enough repertoire of figures, you'll be able to see some sheet music that is new to you, and instinctively know how to perform it.

Developing your repertoire of figures can most easily be approached by having an experienced player model the melodic figure for you, or through tablature or animations showing the requisite fingerings to perform the figure.

Let's apply that idea to a few more short note patterns. The first consists of four notes of the same pitch, which looks like a 'floor'.

The second is a descending sequence, which you might think of as a descending staircase or a child's slide.

Spend some time practising each of these three figures until you can play them without thinking about your fingers. Separate the notes with your tongue and remember that, as you go up the scale, you have to blow harder, and the opposite as you go down.

With that muscle memory in place, it can be applied to reading some simple music. Notice how the figures you've learned are used, and perform them on the instrument.

Learning the note names on the staff

It's possible to read any music just by learning to recognise and perform different patterns. But what if you wanted to tell another musician which note you are playing? That's where knowing the note names comes in.

In Western music, we name the notes using the first seven letters of the alphabet, repeating them for each octave. In the example below, lowercase letters are used for the higher octave.

Technically, which note is positioned on which line is not fixed; a symbol called a 'clef' tells you this. In practice though, the notes are in the same positions because almost all music for the ocarina is written in the treble clef, the squiggly symbol you can see on the left in the staff below.

This clef indicates that the note 'G' can be found on the second line from the bottom. The other notes exist relative to it as described above.

Notes that are higher or lower than those on the five-line staff are shown using ledger lines. This includes the low B and A of 12 hole C ocarinas, as shown below. We do this instead of adding more lines, as the five-line staff is a consistent visual reference. Otherwise, it would be difficult to tell what note is where.

Remembering which note is in which position

You can practice naming notes using this tool, which randomly generates note positions. It is fine to look them up at first:

Learning and practising these positions may also be approached in much the same way as we learned the fingerings: taking small groups and practising them separately.

Breaking them down helps to bring the task within the limits of your short term memory. To practice these, get some blank manuscript paper, and:

- Choose one of these note ranges.

- Write out a line of random notes in the chosen range, saying the name of the note aloud. Don't worry about note durations, just use black circles, or whole notes if you prefer.

- Read them back to a metronome. Say the name in your head while fingering it on your ocarina (use your fingering chart to look it up if need be).

- Ask a friend to write random notes, and then test yourself by reading them, saying the names aloud and fingering them on your ocarina.

A completed exercise would resemble the line below.

There are also some tricks we can use to help us remember some of the note positions:

- The spaces spell the word 'face' from bottom to top.

- The notes on the lines are E, G, B, D, F, commonly taught as Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge.

- The 'blob' at the bottom of the treble clef is roughly in line with the low C ledger line.

Connecting note positions to fingerings

The traditional approach to teaching music reading involves introducing the names of the note positions and teaching the fingerings by name. It is then possible to recognise the name of the note position, remember the fingering of the note from the name, and execute the fingering.

However, this process can be frustrating. It leads to analysing music one note at a time, then stopping to remember the fingering. It is slow, often leads to rhythmic stalling, and creates a playing style with a characteristic 'beginner sound'.

As previously discussed, the goal of learning to sight-read is to subconsciously associate the note positions with fingerings. The intermediate conscious step of naming the notes is something we don't want to be doing, so why practice like this?

There are several ways to practice the direct connection of note position and fingering:

Read a note, perform the fingering

You can practice connecting each fingering directly to its equivalent staff position, without naming it. The practice process is the same as when you learned the note names, but instead of saying the name when you see a given position, you physically execute the fingering on your instrument:

- Break the notes into small groups as before.

- For each group, look up how to finger the note for each position.

- Practice reading until you can subconsciously connect the position to a fingering.

Recognising short sequences

Another option that we did earlier is to practice sequences of three or more notes until they become muscle memory, then connect this with the visual representation of the pattern in notation.

Doing that has the advantage of pushing you to perceive larger groups of notes early in the learning process, and helps avoid the stunted 'one note at a time' sound. It is discussed in Utilising common melodic patterns in sheet music.

Reading by interval

As you were practising playing the patterns introduced earlier in the article, you may also have noticed some things about how the fingering patterns on the instrument relate to the visual patterns found in notation:

- When a note is one position higher than the previous note, we lift one finger.

- When a note is one position lower than the previous note, we place one finger.

This can be used to read music in an approach called 'reading by interval', and is discussed in Playing sheet music at written pitch on ocarinas in different keys.

Bringing everything together

Let's bring everything together and sight-read the following folk tune called Shepherd's Hey:

The first step is looking through the notation for unfamiliar rhythmic or melodic patterns. It's best to identify these and practice them on your instrument beforehand. Thus, when you read through the whole tune, you'll know what to do, and things will flow naturally.

The rhythm should be straightforward, as the patterns are similar to those introduced earlier in the article. I suggest starting by ensuring you can feel a pulse, either internally or using a metronome, and clapping or tapping your foot in time with it.

Next, read and clap the rhythm, ensuring you can perform the whole rhythm without stuttering.

Once the rhythm is in hand, look through the melody and identify the main melodic patterns (listed below). For each one, listen to it and practice playing it on your instrument repeatedly until you can do so without thinking about the finger movements.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Then:

- Listen to the melody and hear how it sounds, while looking at the notation.

- Singing or humming the melody can also help you internalise it.

- Finally, play the music on the ocarina.

This may seem like a lot, but the additional preparation avoids a lot of struggle and frustration. Practising the figures until they become muscle memory, then familiarising yourself with how they look in notation, means that you already know how to perform them. Listening to and singing the melody means you'll know exactly how it should sound.

As you play more music, you'll internalise common rhythms and melodic patterns. Reading new music will require less and less preparation.

Finding music to practice

One of the most common reasons people fail when learning to read sheet music is trying to play something too difficult too soon. When you learned to read, was your first book something huge like The Lord of the Rings? I doubt it.

It's critical to practice music close to your ability, and there's a lot of it available:

- Easy song collections. There are numerous books of easy versions of familiar songs.

- Graded exercises for similar instruments. For example, lower-grade books for recorder can easily be adapted to a single chamber ocarina.

- Folk tunes. Many folk tunes are simple and great to practice with.

Graded music collections are useful, being designed to help you develop your sight-reading gradually. They begin with very simple rhythms and melodies and slowly become more complex.

But note that what has been taught so far includes only the natural notes. As you play a wider range of music, you'll need to learn how to read key signatures, as well as more complex rhythms. These are discussed later in the book.

Playing sheet music above your ability

You may be wondering, 'How long will it take before I can read my favourite song?'

It is possible to start learning to play music of essentially arbitrary complexity regardless of your current ability. All music can be broken down into its melodic and rhythmic figures, which can be learned individually, as we have explored through this article.

I suggest starting by identifying the figures and phrases in the melody. Write out short snippets of the melody with a notation software like MuseScore, play them on repeat, and clap over them repeatedly to internalise the rhythm. Another option is to do the same using a commercial recording and a digital audio workstation.

Then repeat the same process for the melodic patterns, breaking the melody down, working out how to finger these patterns on the instrument, and performing them repeatedly until they become part of your muscle memory. You may find it helpful to go through the music note by note, and write it out in ABC notation.

Once you know how to finger the note sequences and can clap the rhythm, bringing everything together is pretty easy. You may find it helpful to listen to the melody repeatedly and play over it. Eventually, you'll reach a point where you can perform the whole song from memory.

The downside of this approach is that it will take longer than learning something closer to your current ability. It also doesn't develop the general pattern memory that you'd need to be able to reliably sight-read other music of the same complexity.

But the 'I'm actually playing my favourite song' aspect has much value.

Closing notes

We've learned the basics of playing sheet music, and you should now be able to read some basic music, which is awesome. Reading music is primarily a task of associating the visual patterns of notation with a diverse set of muscle memory fragments that enable you to perform the equivalent patterns on your instrument easily.

Getting from this point to being able to sight-read anything is mainly a matter of practice and gradually building up that repertoire of muscle memory. If you experience stalling while playing and need to stop and analyse before you can continue, it is either due to missing muscle memory or an underdeveloped skill in recognising the visual patterns in notation.

The following sections of the book will help you develop these skills, including: