The logic of sheet music

While sheet music can look obtuse and unreadable on first impression, the fundamental logic of sheet music is actually extremely simple. Possibly the best way of discovering this simplicity, is to walk through the steps of reinventing sheet music for yourself.

If you had to design a way of notating music graphically, how would you approach it? We need a way of indicating which note (fingering) to use, how long each note should be played for, and in what order.

You could start with a graph, where vertical position represents the note to play, with higher notes towards the top, and horizontal position representing time increasing towards the right:

But from this alone it is unclear which position represents which pitch. So as the next evolution, you try using some lines, and indicate which note to play by circling the line:

That's better, as it's now easier to tell what note a given circle refers to, but there are still two problems:

- It is hard to recognise which line you are on as they all look the same.

- It is not clear when each note should be played, as there is no horizontal scale.

To address this, you do a few things. First, you realise that you can show twice as many notes if you use both the lines and the spaces to represent different pitches.

Secondly, you decide to only show 5 of the lines, and show notes outside of this range using short 'ledger lines', indicating where the line would have been.

The 5 lines serve as 'home base', giving you a consistent visual reference, so that it remains clear where a note is regardless of how many notes are used.

And finally, you modify the shapes of the notes to indicate different time values, adding a stick to the shorter notes.

This is essentially how sheet music works. Notes are read left to right. Different vertical positions represent different notes on your instrument, and the shapes of the note symbols represent how long each note will last for.

Note symbols

Notes are symbols that tell you what notes to play on your instrument, and also how long each note should be held before moving to the next one.

We use a collection of these symbols, as each one represents a longer or shorter duration of time. The common ones that you'll often see are shown below. I'm sure that you'll have seen the eighth and sixteenth note symbols before as they are frequently used as a visual representation of 'music' in common culture.

The cultural use of these symbols can be a source of confusion though, and whole notes may not look 'right' intuitively.

Notes actually consist of multiple parts, called the stem, head and flags, which communicate different things:

As per the introduction, the note head marks a vertical position on the staff (much like a point on a line graph), telling you what note to play on your instrument. Each position corresponds to a different fingering on your ocarina and a few are shown below. You can find the rest of these in your fingering chart.

The appearance of the entire symbol (head, stem and flags together) describes how long the note will be played for. A whole note consists only of a head. Adding a stem halves its duration, and so on as shown in the previous diagram.

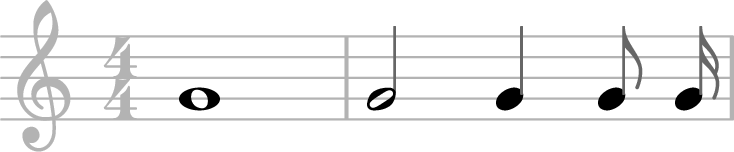

Notes are read left to right, and the following example depicts a series of successively shorter notes, with each next note to the right being half the length of the previous one. We will be exploring this in the next article in this series, Understanding rhythm notation.

The staff and clef

Sheet music tells you which note to play on your instrument, a set of 5 lines and 4 spaces:

The positions on the staff represent the natural notes, A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, repeating in octaves. A symbol called a 'clef' tells you which note is on which line.

Almost all music for the ocarina uses the treble clef, which tells you that the note 'G' can be found on the second line from the bottom:

The other notes are defined relative to this point. If a note circles the space below the G line you take one step down the scale, and so a note in that position tells you to play an F.

And here are the rest of the natural notes that fit within the range of a 10 hole alto C ocarina. You can find out how to finger these using your instrument's fingering chart.

As we noted in the introduction, we only draw a 5 line staff so that we have a consistent reference for where notes are. Notes that are higher or lower are shown using ledger lines, including the subholes of a 12 hole ocarina:

There are a few ways of remembering which note is in which position, which are discussed in the article Playing the ocarina with sheet music.

Reading shapes on the page

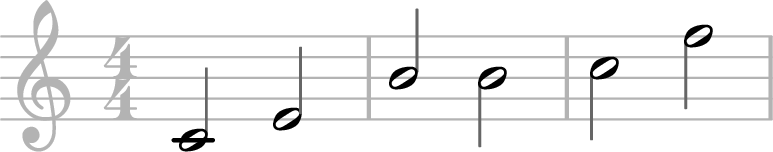

One of the benefits of sheet music is that the heads of groups of notes draw shapes on the page. Take this for example:

Literally it shows the notes G, A, G, d, e, d, but there is another way of viewing it. This is two repetitions of a simple pattern:

- Play a note.

- Play the note one step higher in the scale.

- Play the starting note again.

The notes found in music are not random, and neither are the rhythms. You'll see the same patterns of notes show up over and over in all sorts of music, such as:

By learning to recognise these patterns and how to perform them, we can read music without needing to care about the note names in most cases. See the following articles:

- Playing the ocarina with sheet music.

- Reading rhythms in sheet music.

- Sight reading on the ocarina.

- Playing sheet music by pattern recognition.

Stem direction

- When a note is placed below the middle line on the staff, the stem should go up.

- When a note is placed above the middle line the stem should go down.

- A note placed on the middle line can have the stem going in either direction, depending on what is most readable in context.

The ABRSM music theory workbooks include many examples of 'nitpicky' things like this, and I'd reccomend them if you want to learn about the standard ways of writing music.

Sharps and flats

As we have noted previously, the positions on the staff themselves represent the 7 natural notes:

But if you've read Octaves and scale formation, you'll know that we actually have 12 notes per octave, and that the other notes are named using sharps (♯) or flats (♭).

We also use these symbols in sheet music, and if there is a sharp before a note, you should play that note 1 semitone higher on your instrument.

Sharp and flat notes correspond directly to notes on your instrument, and you can find out how to play them using your instrument's fingering chart.

And, a note preceded by a flat tells you to play the note 1 semitone lower:

Sharps and flats only affect the pitch of the line they are placed on, and are effective until the next bar line:

If the music wishes to return a note back to its natural pitch before a bar line, it will use a natural (♮) sign:

We could use sharps, flats and naturals to notate music in any key, but doing so would get visually cluttered very quickly. Instead we use a key signature, which makes certain notes sharp or flat 'by default'.

Key signatures

A key signature is one or more sharp or flat signs that are placed after the clef at the start of the music. For instance, the scale of G major has one F sharp, and the key signature looks like this:

The placement of the sharp or flat signs within the key signatures of common keys is standardised, and you can see all of the common key signatures below. This diagram is called the circle of fifths, and it organises all of the scales in order of increasing accidentals, with C at the top.

The key signature for any single key always looks the same, with the sharp or flat symbols in the same order, in the same vertical positions. It makes it easier to recognise which notes are used in a piece of music, without needing to scan through the whole melody.

There are several methods of learning how to read sheet music that uses accidentals, and key signatures, which you can read about in the article Sharps, flats and key signatures.

Polyphony (multiple notes at once)

If you run across sheet music where there are several notes stacked vertically, this is a notation of a chord or harmony, telling the player to perform multiple notes at the same time:

![X: 3

M: 6/8

L: 1/4

K: G

[C4 E4 G4] | [G2 B2 D2] [F2 A2 c2] |](/res/abc_converter/sheetmusicchords_48387cfed05cf25163fee6b5095f5710cbeac21d.png)

Obviously, with few exceptions ocarinas can only play one note at a time (monophonic). Generally if you run across notation like this, just play the highest note in the chord as this is usually the melody note. Your ear should tell you if the music sounds right.

When a chord uses a very small interval, the notes in sheet music can't be written vertically like shown above, and instead are 'scrunched together' as can be seen below, and if the note has a stem, a head will appear on both sides of it.

Fundamentally this is showing the same thing, and can be handled in the same way.

![X: 3

M: 6/8

L: 1/4

K: G

[C4 D4] | [G2 A2] [c2 B2] |](/res/abc_converter/sheetmusicchords2_48387cfed05cf25163fee6b5095f5710cbeac21d.png)