Playing Irish music on the ocarina - understanding the types of tunes

Irish music, Irish traditional music, or simply 'ITM', is at the same time dance music and social tradition. It originated as music to accompany communal dances, before the age of recorded music.

Today dancing is less common, and the music more often becomes an opportunity for strangers to play together in informal gatherings called 'sessions', for the joy of playing.

One often also encounters Irish traditional music performed by bands and solo musicians as highly practised performances for an audience, and stage shows like 'riverdance'.

While they are unusual within the tradition as of writing, ocarinas can blend perfectly with the sounds of Irish music, and have a less 'shrill' sound than the tin whistle. They also allow for some ornamental possibilities that are not easily achieved by the idiomatic tin whistle or the simple system flute.

But playing Irish music 'authentically' on the ocarina is more involved than it may appear. First, let's consider what kind of ocarina works best for Irish music.

What kind of ocarina works best for Irish music?

Irish music is usually played in the keys of one or two sharps (D, G, and their modes), and the majority of tunes fit within a range of an octave and a sixth, spanning from D to B in the second octave.

As noted above, Irish music is widely played in group 'sessions' where numerous people play in unison, and this range is dictated by the limitations of other instruments used, like D tin whistles, fiddles, diatonic button accordions, mandolins, bazukis and guitars.

To be able to fit in using a multichamber ocarina is practically mandatory. In principle a typical C double ocarina would work and can play the required range of notes, but you may find chamber switching to be a burden. Irish music is played with notes whizzing by at a high rate of knots.

Personally, I use a Pacchioni system double in D for playing Irish music as its range perfectly covers the required notes. In this system, the second chamber is tuned one octave above the first, meaning there are several overlapping notes between the chambers (less need for chamber switching), and the chamber break on D also aligns with the octave break on a D whistle or flute.

But I only have a single chamber ocarina?

If you only have a typical single chambered ocarina you aren't out of luck, there are some tunes that will fit, some of which can be found in my collection of common Irish tunes for a single chambered ocarinas:

A collection of Irish music for single chambered ocarina >

Most of these tunes require the full range of an ocarina tuned in D (D to G approximately). If you only have an ocarina in C, you'd be limited to playing tunes in the range D to E, an octave and one note, which considerably reduces the repertoire.

It is possible to transpose the music down by a whole tone to better suit a C ocarina if playing alone, and this will give you the correct fingerings to use on a D ocarina. I do not recommend 'transposing to fit' in an Irish music session though, as the other musicians won't be able to join you.

Finally, I DO NOT recommend using any kind of pendant (4,5,6 hole) ocarina if you are serious about playing Irish music, as they don't have the needed range, and offer little scope for ornamentation.

Sounding pitch

Note that because Irish sessions include an assortment of different instruments with a variety of tunings, instruments are always thought of at sounding pitch. For instance, if someone is playing a D whistle they are thinking about the scale as 'D, E, F sharp etc'—instruments are never 'transposing instruments'.

It is HIGHLY recommended to learn to read at written pitch. Playing Irish music requires learning a very large number of tunes off by heart.

The types of tunes

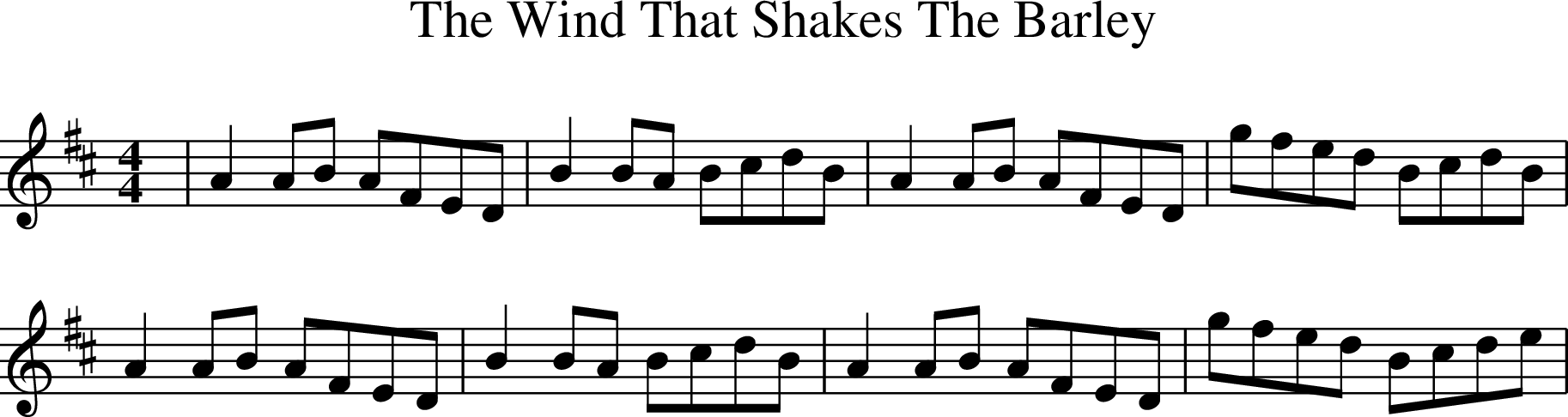

You may have encountered terms like 'jig', 'polka' and 'reel', which refer both to a type of tune, and the class of dance they were written to accompany. Over time, many kinds of tune and dance have evolved, and in many cases, you can do different dances to the same tune.

And yes, we call them 'tunes', not 'songs', because they are not meant to be sung. Most of them have never had lyrics. This is in contrast to vocal music traditions like ballads, Sean-Nos airs and drinking songs, which naturally are songs.

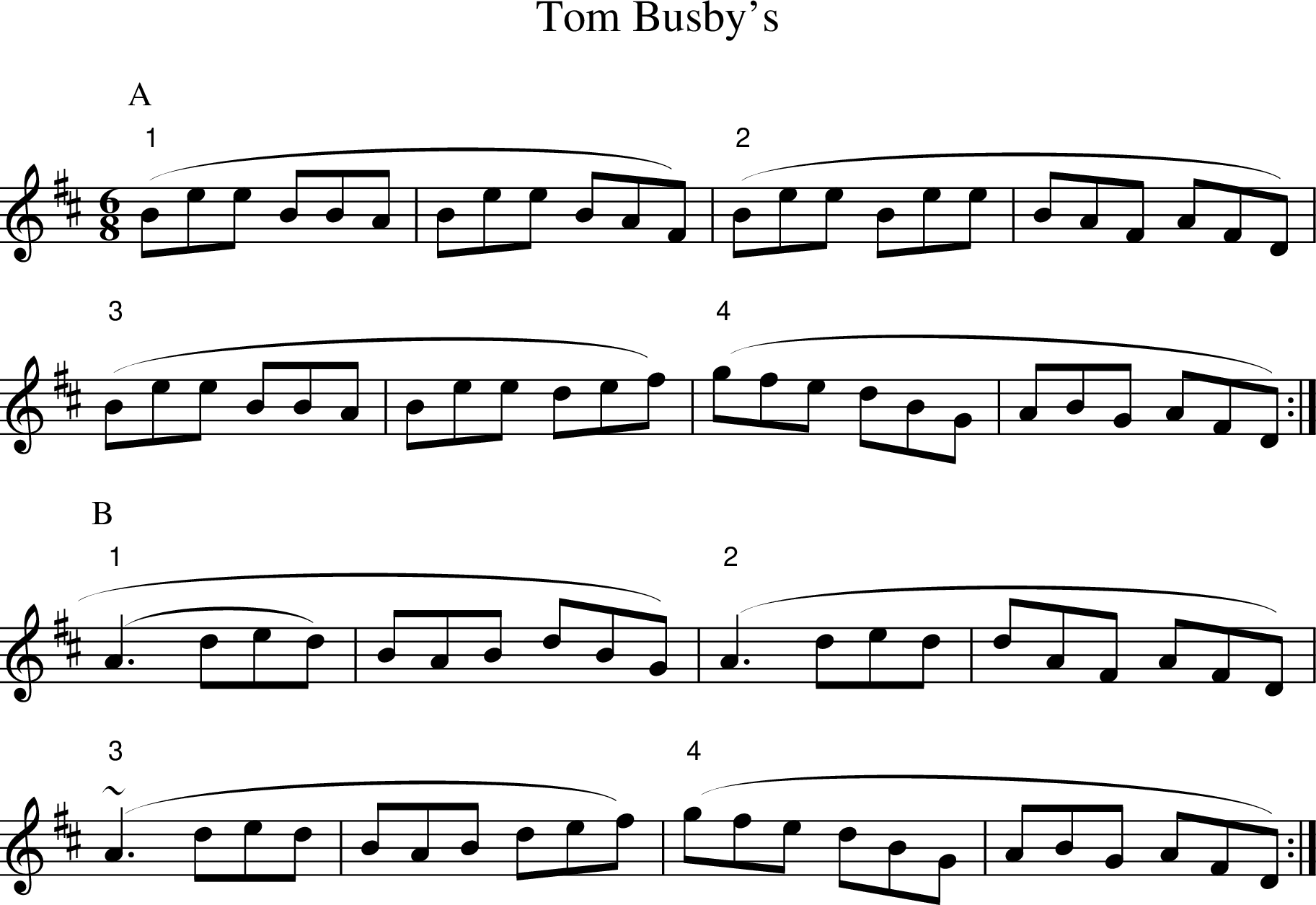

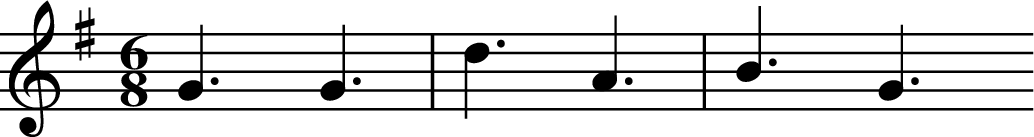

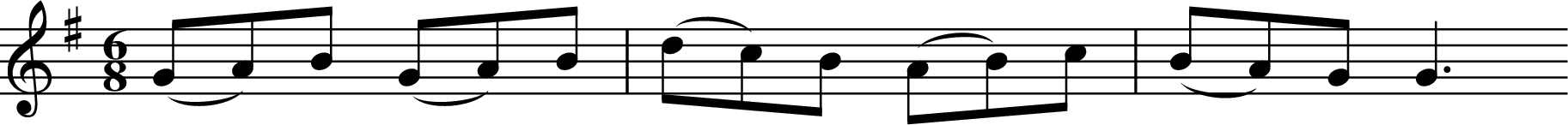

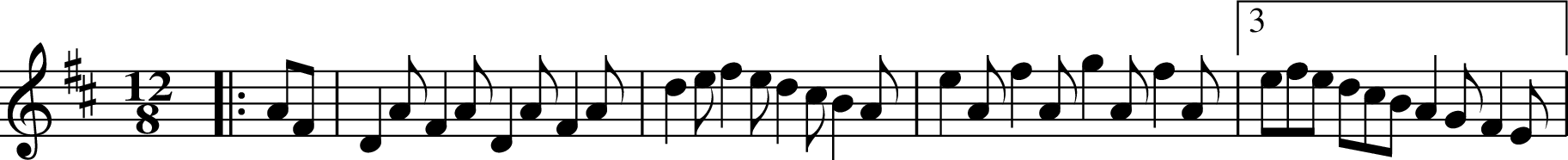

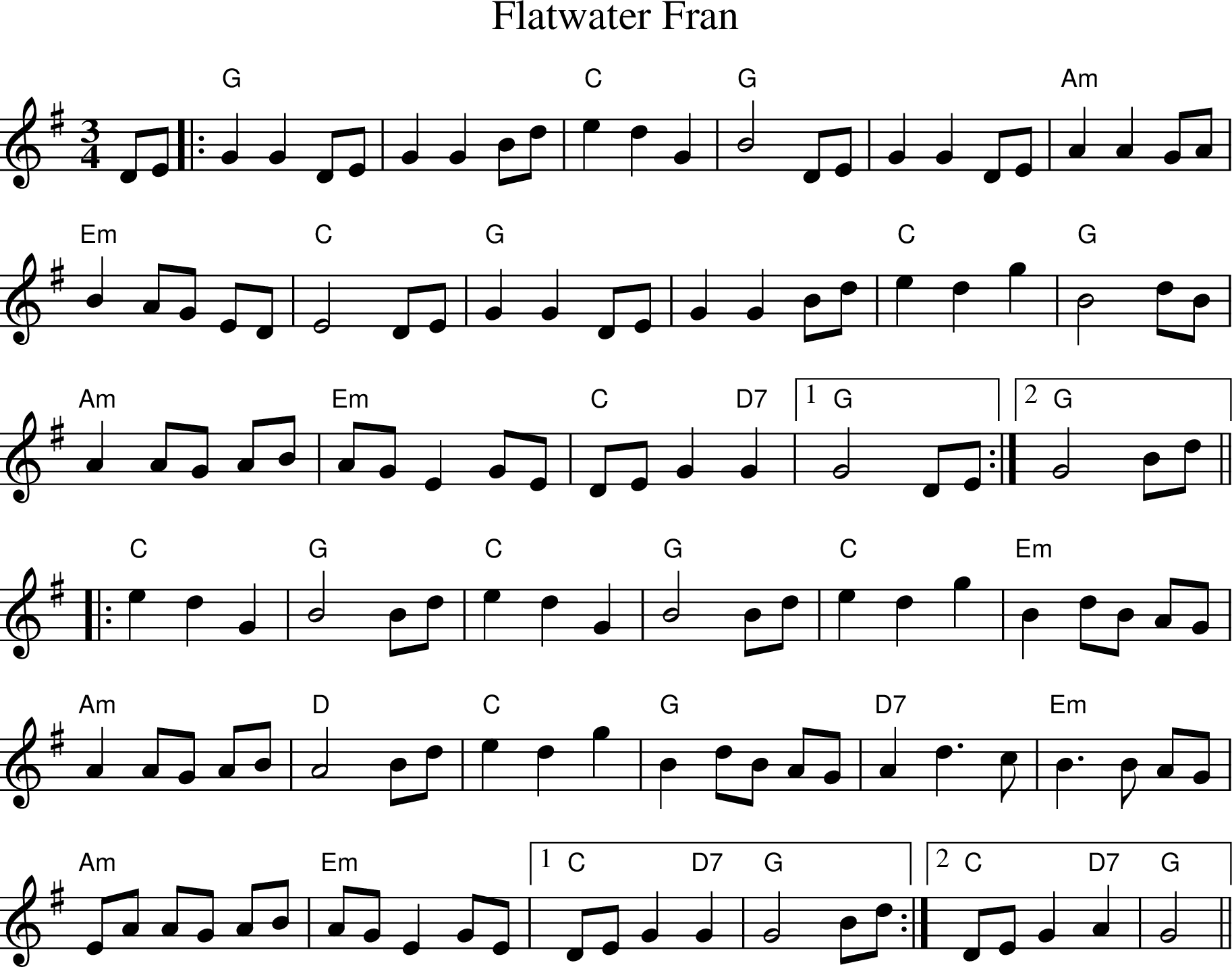

Tunes are generally structurally rigid, having parts we call 'A' and 'B', which are usually repeated once, this for instance is a jig, which will be discussed in more detail later:

There are numerous different kinds of tune which can be differentiated mostly by how they subdivide the beat. Lets explore this for some common types of tune:

Polkas

The polka is originally a Czech couple dance which spread throughout Europe in the 1800's, but today polka tunes are used for backing many different kinds of dance, from group ceilidh dances to Irish step dance, or as instrumental session tunes.

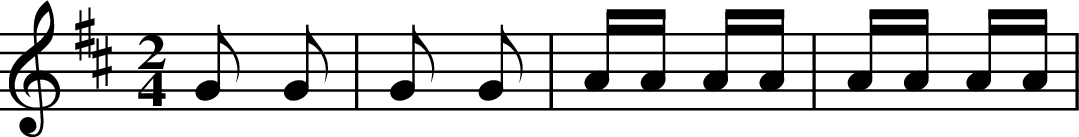

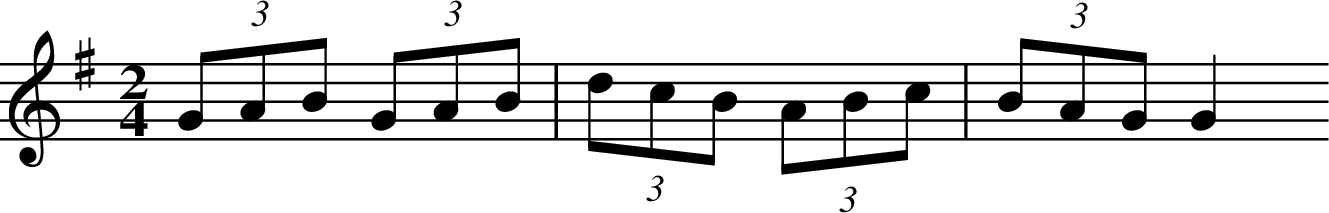

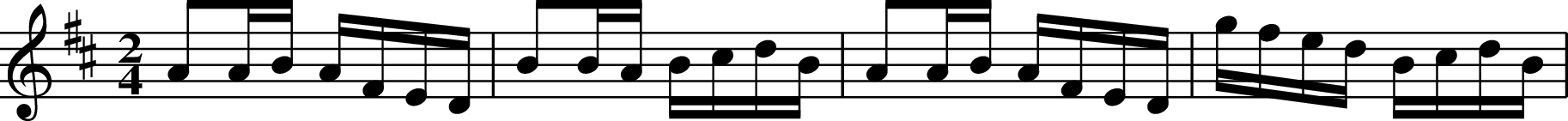

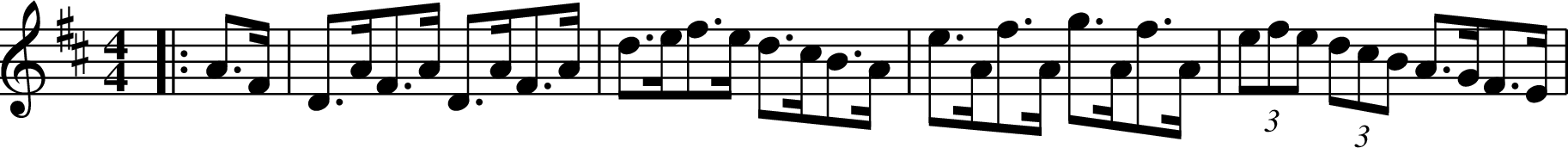

Polkas are based on groups of two beats (2/4), which are often divided into 8th notes.

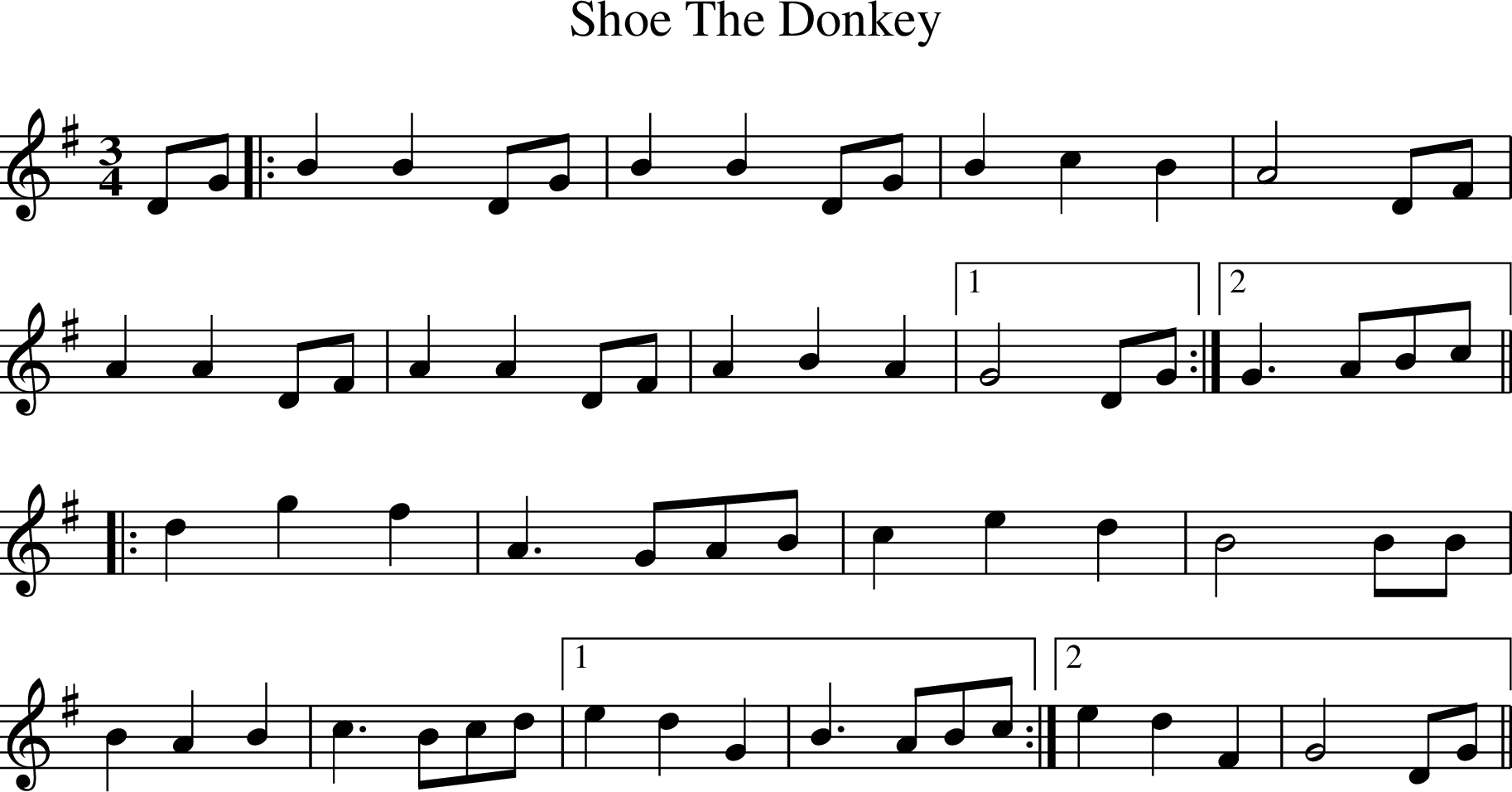

Most Irish polkas are straightforward to play and often serve as beginner tunes. The following tune is a simple example which fits in the given key on a G ocarina, rhythm performed as written.

Polkas in Irish music can be played with the rhythmic accents on the beat, off the beat, and commonly varying between the two. Its unique from playing styles in continental Europe where the off beat accent is more common.

A flute or fiddle player would achieve accents by pulsing their volume, but on ocarina we can instead very how we tongue and slur notes, For instance if you slur adjacent notes, the tongued note tends to sound more prominent.

Playing style and ways of emphasising and de-emphasizing notes will be discussed more in a future article.

Jigs

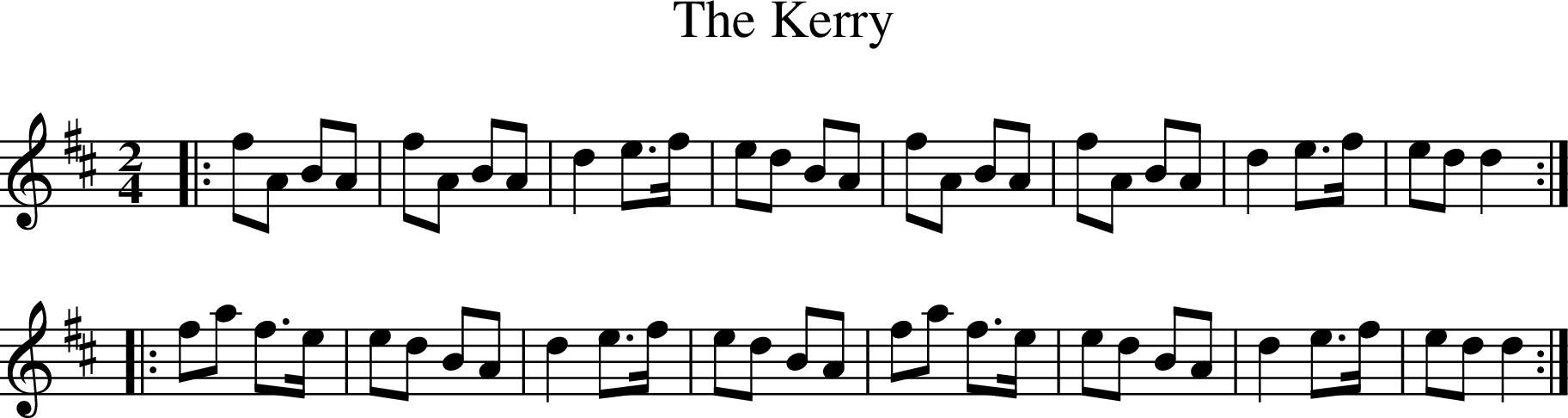

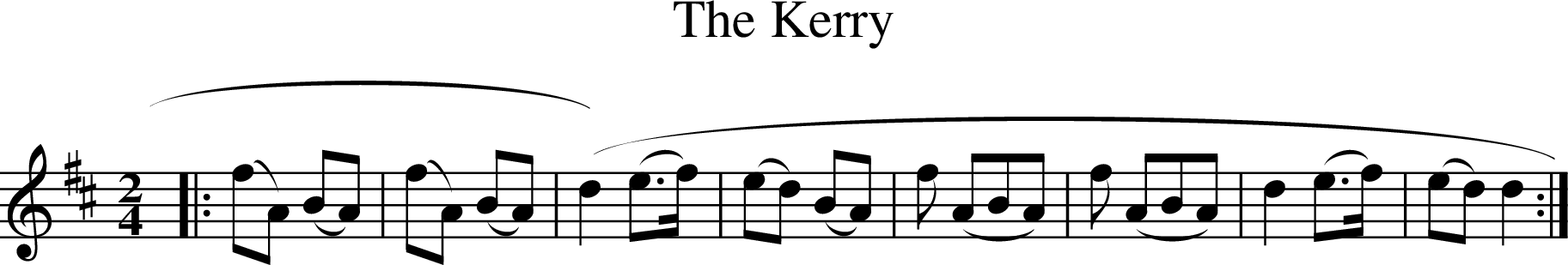

Jigs are a mainstay of traditional music and are common in the Irish, Scottish, English traditions. Like the polka a jig is a tune based on groups of two beats, each of which is split into 3.

Considering a jig is a tune based around two beats, you may find it confusing to see them written in 6/8. It's just a notational convention called 'compound time', representing two dotted quarter notes, because people didn't want to include a fractional value in a time signature for some reason.

Though you could think of this as 2/4 time where each quarter note is a triplet:

Most jigs are comprised almost entirely of 8th notes, and each triplet is clearly visible due to the beaming of the notes.

The rhythm of a jig is emphasised in playing by lengthening the first note in each group of 8th notes, and the other two notes being shortened into the remaining time. It's easiest to get the hang of by listening to experienced musicians. It is practically impossible to notate.

Irish music also varies where the beat emphasis is within jigs throughout the tune. You commonly hear them played with the first note emphasised, which can be done by slurring groups of 3 notes.

Jigs sometimes get played with a 'lift' on beat 3, which can be achieved by slurring adjacent notes.

There's a great deal of complexity in how these are performed and the best approach to developing a feel for it I think is to listen to and imitate experienced players of flute or whistle.

Note that you often breathe in a jig by dropping the middle note in a triplet.

Reels

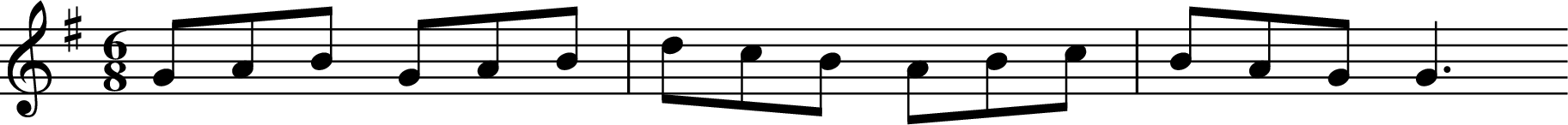

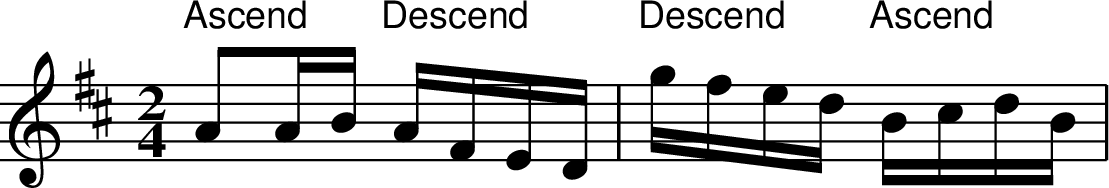

It is easiest to understand reels relative to polkas and jigs. A polka is a tune in 2/4 which divides each beat into 2 8th notes. A jig divides each beat into a triplet. Reels go one step further and divide each beat into 4, something like this:

Notated in this way it is easy to see where the note emphasis should lie. if you where to count this '1 - e - & - a - 2 - e - & - a', the notes corresponding to '1' and '2' are where a dancer would feel the beat / pulse of the music.

Having many subdivisions and a high rate of notes gives reels a very lively feel. They are only played at around 110BPM for dancing yet they sound a lot faster.

However reels are most often notated in 4/4 time, which poorly reflects how they are actually played. At typical playing tempos, 1 note per quarter note would give you 210bpm, which is kind of ridiculous.

Another way to show the same thing is to use 2/2 time. This is structurally equivalent to 4/4, but more clearly states that there are only two beats per measure.

Note emphasis in reels is mostly on the '1', '2' to carry a strong driving rhythm for dancers, and in the above video, they are varying their volume in order to carry this pulse. Such is also common in the structure of the notes, inverse motion and other pitch discontinuities aligning with the beat.

Despite being composed mostly of quarter notes Irish music often has a syncopated underlying rhythm, the emphasis is placed on off beats using contrary motion. I.e. second part of humours of trim.

Hornpipes

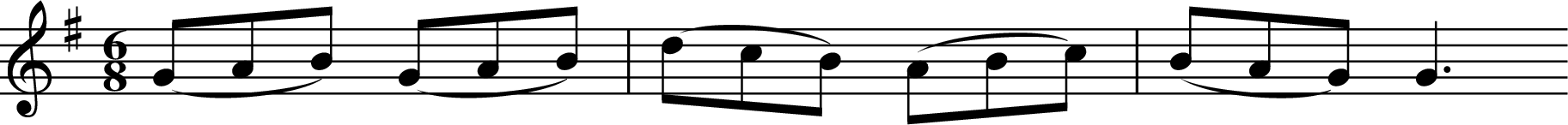

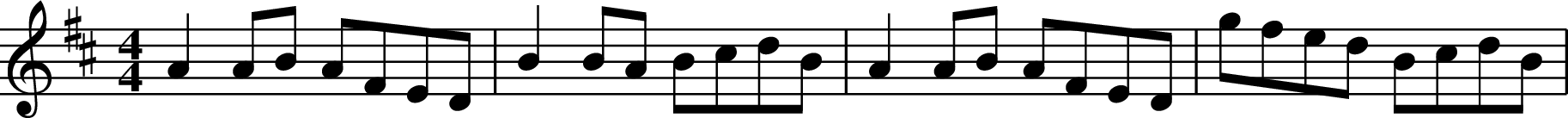

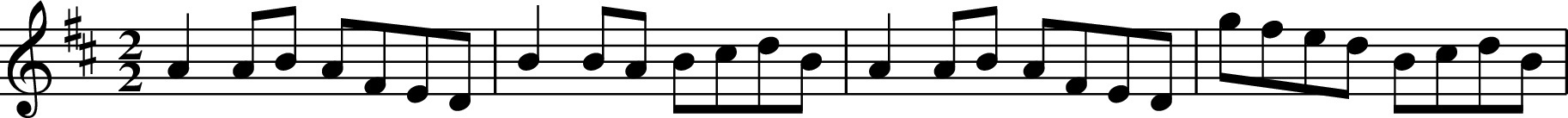

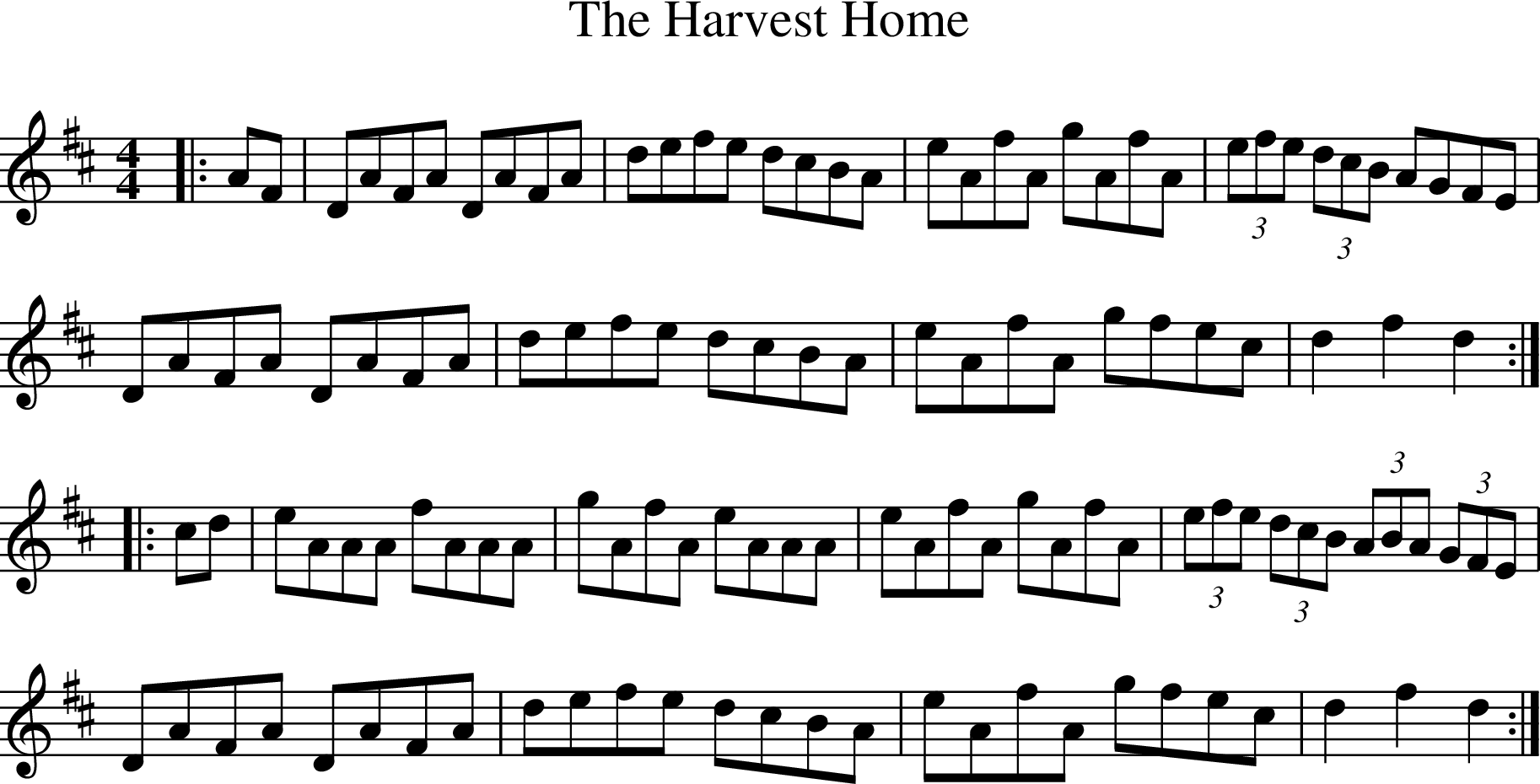

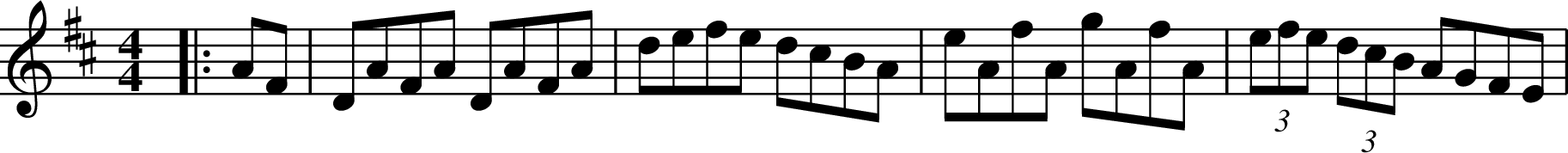

Hornpipes are a somewhat extreme example of tunes not being played as the notation suggests. Hornpipes are written in straight 4/4 time as follows:

But when performed, the rhythm is 'swung' so that each pair of 8th notes, the first is approximately twice as long as the second. This could be more accurately noted in 12/8 time as follows. Though do note that the exact rhythm can vary from this, and is best learned by listening to performances, or playing with others experienced with traditional music.

And sounds like this:

They are rarely swung to the point of a dotted rhythm in 4/4. As this rhythm is consistent throughout the whole tune it is typically omitted in notation. It is assumed that people know how to play a hornpipe.

Common factors that differentiate hornpipes from reels is that hornpipes are slower, often include leaping patterns to pedal notes, and include 'true' triplets. A triplet if included in a reel is most often played '16th 16th 8th'.

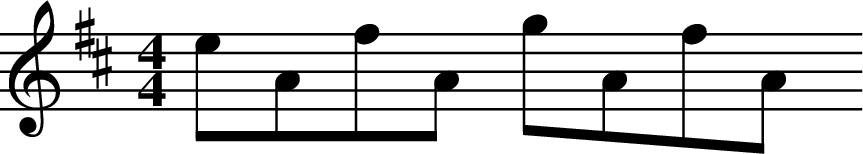

Another thing, hornpipes often contain sequences like the following, where the tune repeatedly jumps down to a lower note. On the fiddle (violin) this is played by dipping the bow to sound the open A string. It is effective on that instrument because the open strings will ring long after they are played. Consequently it is a form of harmony and anchors the tonal centre of the phrase.

Performing this on the ocarina can be tricky because the pitch of the low note can tend to wander. Practice the sequance slowly using a tuner or referance drone focusing on getting it correct, then speed it up.

If you're playing with other people, it also works to omit the pedal note like this:

Slip jigs and slides

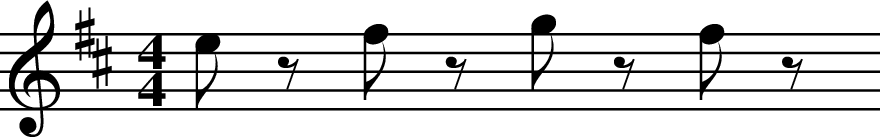

Both of these tunes are based on the same kind of triplet rhythm as a jig. A slip jig is based on 3 triplets (3 beats), and sounds something like this:

Slides are based on 4 triplets, and are generally a lot less rhythmically dense.

Waltz

A waltz is a slow partner dance in 3/4 time. The tunes place emphasis on the first beat of the measure and are played as written.

Mazurka

It is important to note that not everything in 3/4 is a waltz, and the Mazurka is one example. While a waltz places emphasis on the first beat, the emphasis in a mazurka is on the second or 3rd beat, or both.

When it comes to playing mazurkas, I'd recommend starting by learning the basic dance figures. The first of these is a '1,2,3 - 1,2,3' step where the 'one' count alternates between left and right similar to a waltz.

The second step you find in mazurkas is a '1,2,hop', starting on the left or right, shifting to the opposite foot, and then hopping or 'pulsing' on the same foot on beat 3. If you do several of these in sequence, the 'lift' remains on the same foot.

A basic danced mazurka alternates between the two figures, '1,2,hop - 1,2,3', or the opposite depending on what fits the music, however it is an improvised dance and they are often performed in various orders, and other figures introduced for variation.

Mazurkas are pretty rare in Irish music and dancing today, but numerous examples can be found within French traditional dancing, and that of other parts of continental Europe. This style of dance is broadly called 'balfolk'.

Once you've got a feel for the dance steps, it should be pretty easy to relate this to how you'd play the music, with longer notes in a tune implying the figure with a 'hop'.

Tunes that change flavour

It's not uncommon to find people playing one type of tune as a different kind of tune, for instance taking a hornpipe and playing it like a reel, or taking a jig and playing it as a waltz.

A good example is a tune called 'crested hens' often played in Irish sessions as a waltz, which was originally a French 3 time Bourée. Although to me Crested Hens is a very strange waltz, because the note patterning in a 3 time bourée tends to emphasise notes 1 and 3, where a 'traditional' waltz only emphasises note 1.

There are certain characteristics to the notes of different kinds of tune beyond just tempo and note emphasis, which will become apparent with experience.

Moving forward

Now you should understand the different types of tunes and have some idea what it is you're listening to if you hear some Irish music. If you'd like to learn more about different types of Irish tunes, I'd recommend the following article:

A comprehensive guide to Irish tune types

Sheet music for hundreds of tunes are available for free on the website https://thesession.org, One thing you may notice is that this sheet music includes very little in the way of stylistic guidance.

Irish music is an aural tradition, meaning learned by ear, and stylistic details are added by the player from their own experience. It is rather impossible to notate, because different players approach it in different ways, we'll be exploring playing style in the next article in this series.